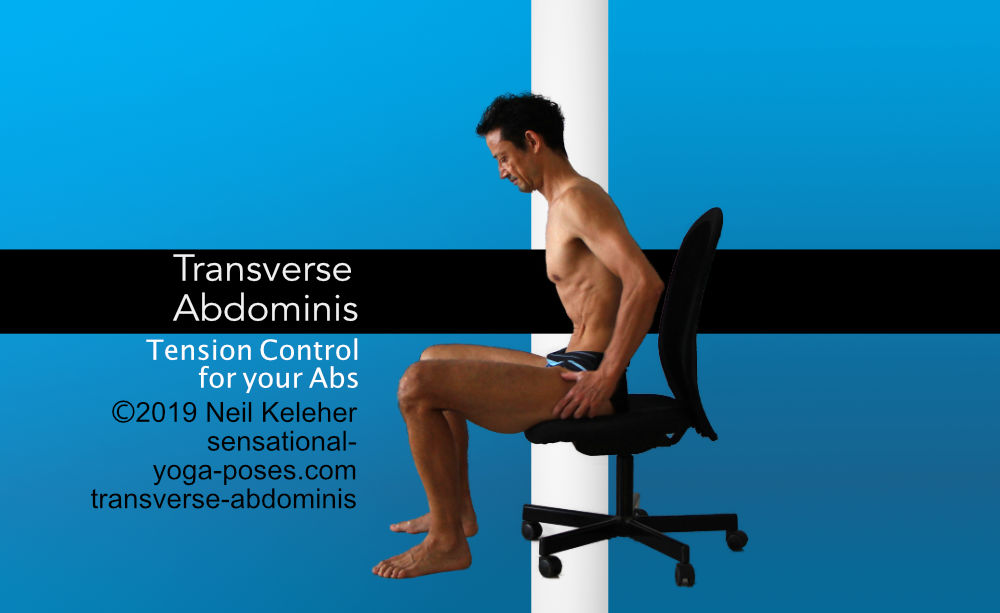

Why learn to activate your transverse abdominis?

Activating the transverse abdominis can help to stabilize your SI joint, your thoracolumbar junction and the low back in general. It can be used to help to anchor your hip flexors (the "long hip flexors", which attach at the ASICs) and provide support for some arm movements. It can be used as an initial activation mechanism for stabilizing the core.

It can also activate the rectus abdominis and external obliques as a side affect.

How the transverse abdominis can be used to stabilize your core

When you pull your belly in past the border of your ribcage and hip bones, you are actually lengthening your rectus abdominis, external obliques (and internal obliques). If you pull in slowly and smoothly, and can feel your belly pulling in, chances are these muscles are resisting the contraction of your transverse abdominis.

With the rectus abdominis and obliques working against the transverse abdominis, this then helps to stabilize your ribcage, lower back and hip bones. You get "core stability" almost for free.

Using the transverse abdominis to stretch the diaphragm

When you pull your belly inwards using your transvers abdominis, you are also lengthening the respiratory diaphragm.

And so you can also resist the inwards pull of the transverse abdominis by activating the respiratory diaphragm against it.

Increasing core stability via the iliocostalis and longissimus muscles

When pulling your belly inwards, you can increase the resistance of the external obliques and rectus abdominis to the transverse abdominis by also activating iliocostalis and longissimus.

These are sub-groupings of the spinal erectors that attach to the backs of the ribs. In some cases both ends attach to ribs at either half of the ribcage, in other cases, they attach to the backs of the ribs from the back of the hip bones (iliocostalis) or sacrum (longissimus).

Note that the spinal erectors that attach directly to the spine (and the smaller intersegmental posterior spine muscles) will also activate.

A good "hint" that you are activating these muscles is that you can feel a downwards pull (towards your hip bones) on the backs of your ribs.

An additional benefit of using these spinal erectors to augment core stability is that because you are using your abs against your spinal erectors you have the option of shaping the spine, bending it forwards or backwards (or sideways) or twisting it to suit whatever overall action or position you are working towards.

Now you could achieve this without the transverse abdominis, but if you like efficient or effective actions, it's worth your while to learn how to activate your transverse abdominis. And you can then experience first hand for yourself, in any situation, whether it helps to activate them or not.

Improving transverse abdominis control via Agni Sara

One of the first exercises I learned for activating the transverse abdominis is called Agni Sara. (There are several exercises called Agni Sara).

The exercise involved pulling the belly inwards one section at a time working from the bottom upwards, then releasing the belly one section at a time working from the top downwards.

(For this exercise, you can divide the belly into approximately six horizontal sections!)

Often times I'd practice while sitting on the toilet. Somehow it was a little bit easier then, perhaps because my belly was so relaxed.

Using the pelvic floor muscles and the transverse abdominis to stabilize the SI joints.

A simple way to activate the lower band of the transverse abdominis, and stabilize the SI joints and lower portion of the lumbar spine at the same time is to activate the pelvic floor muscles.

The lower band of the transverse abdominis is the portion that spans the front of the hip bones.

Where the pelvic floor muscles can be used to pull the ischial tuberosities (sitting bones!) inwards (and the bottom tip of the sacrum forwards), the lower band of the transverse abdominis opposes this action by pulling inwards on the ASICs.

Working against each other, these sets of muscles help to stabilize the SI joints and also the lower portion of the lumbar spine.

For a stronger activation, you may find that it helps to activate the pelvic floor muscles first. The lower band of the transverse abdominis will then activate automatically in response.

You could try to activate the lower transverse abdominis first by creating an inwards pull on the ASICs and inguinal ligament. However, the activation may not be as strong.

Resisting the Lower Transverse Abdominis for SI Joint Stability

Part of what resists the action of the transverse abdominis at the back of the sacrum is a layer of connective tissue called the Thoracolumbar Composite. It's part of the Thoracolumbar fascia.

It is a fused mass of connective tissue made up of layers from the erector spinae aponeurosis and various other layers of the thoracolumbar fascia. This composite connects to both sides of the back of the pelvis on either side of the sacrum.

When the Transverse Abdominis engages, the Thoracolumbar composite resists the back of the pelvis being pulled apart. The ischial tuberosities spread apart instead.

Anchoring the spinal erectors and multifidii

The thoracolumbar combosite forms a pocket with the back of the sacrum. The spinal erectors, and the smaller posterior spinal muscles like multifidus are sandwiched within this pocket between the back of the sacrum and the thoracolumbar composite.

Some fascicles of the multifidus attach to the front surface of this layer of fascia and so when tension is added to this fascia by the action of the lower transverse abdominis these same muscles have a firm foundation from which to create a downwards pull on the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae to which they attach.

Note that this tends to cause the sacrum and lumbar spine to bend backwards. Activation of the rectus abdominis and external obliques tends to oppose this action by creating a forward bending force on the spine. And so here again we have a mechanism for increasing core stability, instigated by activation of the transverse abdominis.

The Transverse Abdominis and the Quadratus Lumborum

The connective tissue (or aponeurosis) of the transverse abdominis passes behind the Quadratus Lumborum muscle before attaching to the lumbar vertebrae.

The QL attaches to the back of the pelvis and from there its fibers reach up to attach to the transvers processes of the lumbar vertebrae and the lowest pair of ribs (the 12th pair).

A second layer of this muscle also sometimes exists and has fibers in the opposite direction reaching down from the lowest pair of ribs to attach to the lumbar vertebrae.

I had the thought, that because the transverse abdominis passes directly behind the quadratus lumborum before attaching to the lumbar spine, that tension in the TA could cause tension in the QL. I don't know if there is enough give in this portion of the TA to add tension to the QL or not, but at the very least tension in the TA could act as a signal to the QL to activate or relax as required.

The Upper Transverse Abdominis and Serratus Posterior Inferior

I never gave much thought to the upper transverse abdominis until some experiences in a Qi Gong class and some pain at the junction of my thoracic and lumbar spine during forward bends.

I felt pain in the region of T12/L1 (the bottom of the ribcage) in forward bends, particularly when I wasn't focusing on lengthening my spine or on using my arms.

Why didn't I just lengthen my spine and reach with my arms? Because I wanted the option not to have to do that.

And thus I started to explore the Serratus posterior inferior, a group of muscles whose fascicles reaches down from the lower three or four ribs to attach to the spinous processes of the two lower thoracic and two upper lumbar vertebrae.

I found that I could activate this muscle (with a reasonable degree of surety) with a combination of first lifting the backs of the ribs and then creating a downward pull on the lower three (or four) ribs. In the process of experimenting with this I discovered that it caused the upper band of the transverse abdominis to activate.

This was important in the Qi Gong class I attend since I then found it easier to take impacts to the solar plexus.

Using Transverse abdominis to anchor the hip flexors

There are three hip flexors that attach at or near the ASIC. These long hip flexors work on both the knee joint and the hip joint and include sartorius, tensor fascia latae and rectus femoris.

Since all of these muscles attach at or near the ASICs, and since from there they reach downwards to attach to the tibia, one way to anchor these muscles is to create an upwards pull (or opposing pull) on the ASICs. You could do this by creating a downwards pull on the ischial tuberosity.

Another option is to create an upwards pull via the external obliques, which has fibers that attach to the ASIC. Another option is to pull inwards on the transverse abdominis.

As already mentioned, it will pull inwards on the external obliques (as well as the internal obliques and rectus abdominis). This lengthens the external obliques, adding tension to it by stretching it. In turn the obliques can activate to resist this stretch. In either case, an upwards pull o the ASICs is generated, thus providing anchoring for the hip flexors.

Using the transverse abdominis to also anchor the gracilis

The gracilis could also be considered a hip flexor. It's also an adductor. In any case, it, like the long hip flexor muscles, works on both the knee joint and hip joint. It attaches to the hip bone near the pubic bone.

To anchor it, you could again create a downwards pull on the ischial tuberosity or even the PSIC. Another option is to create an upwards pull on the pubic bone via the rectus abdominis and/or the external obliques.

As with generating an upwards pull on the ASICs, here too you can simply activate the transverse abdominis to pull the rectus abdominis rearwards, thus stretching it. If this muscle is activated, the upwards pull on the pubic bone can be augmented.

The Iliacus and pectineus

The iliacus and pectineus could also be considered as hip flexorsThese muscles can also be anchored with an upwards pull on the ASIC and or the pubic bone.

Anchoring the psoas with the transverse abdominis

The psoas is another multi-joint hip flexor. It works on the lower back and the hip joint.

To both anchor it at the lumbar spine and to also give it length or pre-stretch, it can help to flatten the lumbar curve. Note that this tends to happen naturally whenever the rectus abdominis and external obliques are engaged. And so one way that you can use the transverse abdominis to also anchor the psoas is to use it to pull the belly inwards while at the same time allowing (or causing) the lumbar spine to flatten.

Note that you can do this by pulling down on the front of the ribcage or pulling up on the front of the hip bones. So that the aforementioned hip flexors are also activated, in most cases you may be best served by lifting the front of the hip bones in order to flatten the lumbar spine.

More on the transverse abdominis

For more on the transverse abdominis you can read: Transverse abdominis function, Transverse abdominis exercises: (Training All Three Bands of the Transverse Abdominis), Transverse abdominis training: (Understanding How the Transverse Abdominis Interacts with Other Muscles).

Published: 2020 08 16