Shin rotation relative to the knee when the knee is straight

When the knee is straight, the shins have a severely limited ability to rotate relative to the thigh bones. I used to say that the shin can't rotate relative to the thigh bone when the knee is straight but I think I may have been wrong. There may be some slight ability to rotate, enough that controlling "rotation" of the shin relative to the thigh is still important when the knee is straight.

(In the same way, I used to be under the impression that the lumbar vertebrae can't twist relative to each other. While the amount is limited, there is some movement, enough that controlling this rotation is still important.)

If you tend to get a collapsed arch while walking, the knee can be straight or nearly straight and so this idea of shin rotation relative to the knee can be important.

Put another way, it can be helpful to think about controlling the rotation of the shin relative to the knee, even when the knee is straight, or nearly so.

Biceps femoris short head actions when the lower leg is fixed

Assuming that the lower leg is fixed, then the short head of the biceps femoris can help to rotate the thigh relative to the lower leg bones.

Because the thigh attaches to the rest of the body, this might seem not very likely, but it's still something to bear in mind. In a lunge, with the front foot stable, the biceps femoris could work from the shin bone to pull the femur outwards. What could then happen is that the knee moves inwards.

A way to play with this idea, and test it, is to try activating the short head biceps femoris while sitting with your feet on the floor. See if you can use it to cause your knee to move inwards.

Controlling shin rotation using the biceps femoris short head

For myself I occasionally get problems with my left foot in particular. That my left knee was injured in a motorcycle accident may or may not be relevant. (At the time I believed I'd ruptured or at least injured the ACL.)

I have a lot more difficulty maintaining the arch of my left foot than I do that of the right foot. What tends to happen is that my left shin rolls inwards slightly, the heel collapses in wards as does the arch of the foot.

And while I learned foot exercises (using muscles of the feet and ankles) to help correct my fallen arches a long time ago (I had to hide my fallen arches to pass the army medical), and subsequent to that learned how to also support external rotation of the shin via the long hip muscles, neither seemed to help in this instance.

Something I'd failed to consider till now was controlling rotation of the shin relative to the thigh using local muscles like the biceps femoris short head, a muscle that works across only one joint.

One possible reason for my collapsed arch was that the biceps femoris short head on that leg isn't functioning ideally.

Giving the biceps femoris a fixed anchor point for effective functioning

Generally when a muscle fails to function (and it isn't due to a recent injury) the first thing I look at is how to give the muscle in question a fixed end point.

My thoughts were that to give the biceps femoris a fixed end point it needs a femur that is externally rotated or at the very least resists internal rotation.

With the femur under the above conditions, the biceps femoris short head can act effectively to create an external rotation on the lower leg.

Anchoring the bottom end of the Biceps femoris

In a previous article (or articles) I've mentioned how creating a downwards pull on the fibula can help to anchor both the long head and the short head of the biceps femoris.

The peroneus longus, peroneus brevis, soleus, and tibialis posterior all attach to this bone and any of them, when active, can be used to create a downwards pull on that bone.

Note that these same muscles can be used in concert to help shape the foot and unflatten collapsed arches.

How to anchor the top end of the biceps femoris?

With the femur under an external rotation force the biceps femoris can act to create an external rotation force of the fibula, and additionally resist any downwards pulling forces on that bone thus giving the aforementioned muscles that unflatten the foot a stable anchor point from which to do just that, unflatten the foot (or "un-collapse" the inner arch of the foot).

The question then was, which muscles did I need to work on to create that external rotation force on the thigh bone?

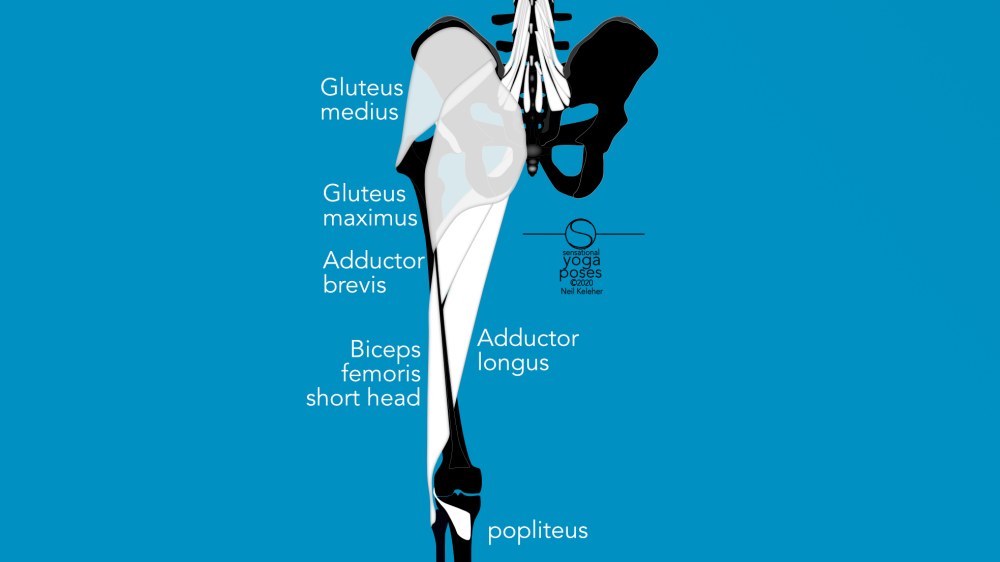

Gluteus maximus

An obvious candidate for externally rotating the thigh bone is the deep fibers of the gluteus maximus. These fibers run from the back of the hip bone (and possibly the sacrum) to attach to the back of the femur. Interestingly, the line of attachment of these fibers ends just where the line of attachment for the biceps femoris short head begins.

Adductor brevis and longus

Other muscles that can create an external rotation force on the thigh relative to the hip are the adductor muscles (adductor brevis, adductor longus, adductor magnus (but not the long head of that muscle)).

These adductor muscles all attach to the back "edge" of the femur.

The adductor brevis, which attaches to a span that covers the upper half of the back of the thigh bone may be a likely candidate. At the hip bone, it attaches near the pubic bone.

The adductor longus may also be a candidate, though it attaches lower on the back of the thigh than the adductor brevis.

Working together

Now it could be that all of these muscles (deep fibers of gluteus maximus, the adductor brevis and adductor longus) can work together to create an external rotation force on the thigh.

Why together?

Because where the adductor longus and adductor brevis both attach near the front of the hip bone, potentially creating a force that flexes the hip joint, the deep fibers of the gluteus maximus attach to the back of the hip bone, potentially creating a force that extends the hip joint.

Bringing in the gluteus medius

Note that the adductor longus and brevis also work to adduct the hip. However,the deep fibers of the gluteus maximus may not help to help to resist by abducting, because the fibers cross the joint in such a way that they don't affect adduction or abduction, at least not while walking.

But the gluteus medius is an adductor. And so it could activate also.

And the gluteus maximus has fibers that attach to the fascia that covers the gluteus medius. So if gluteus medius activates first, then those particular fibers of the gluteus maximus have an stable anchor from which to act on the femur.

(Note the interconnections here. This is one reason why I use a bicycle wheel as a metaphor or model for the hip joint. It makes it a little bit easier to understand how all the muscles of the hip can relate and work together.)

Putting it all together

Putting this all together while walking, the first thing I do is work at creating an external rotation force on the thigh. And there I'll get some butt activation (gluteus maximus). But I'll also get some sensation along the top half of the back of the thigh (adductor brevis).

From there I'll create an external rotation force on the fibula.

What I've found, in limited testing (walking a for a few minutes while tired) is that it's then easy to maintain the arch of my problem foot while walking.

Proviso

Note that this isn't to say that I'll have to use this particular sequence of muscle activations all of the time.

I tend to find that for the various problems I've had, different muscle activations work at different times. And whether this is just because the body naturally tends to switch references, using different bones or areas of the body as a stable anchor point to give the body active rest, or whether a particular muscle activation has reset the brain, but in the process uncovered another problem, I'm not sure.

But the more flexible I am in sensing my body and controlling it, and the less attached I am to one particular way of using my muscles, the easier it is to come up with a fix for whatever problem I'm dealing with.

The difference between creating an "external rotation force" and "externally rotating"

On another note, I use wording like "creating an external rotation force" instead of "externally rotating" to emphasize the creation of force versus movement.

You can create an external rotation force whether the thigh is internally rotated or externally rotated. The idea in focusing on the force (and the muscles that create that force) is to bring focus to the idea that the positioning isn't always as important as the forces that are created.

So with regards to fallen arches and a non-anchored short head biceps femoris, I should be able to maintain the arch of the foot whether the thigh is internally or externally rotated relative to the hip. Being able to create an external rotation force in any of these positions should allow me to do that.

Learning to drive your body

One other point is you may find that with enough practice you no longer have to focus on activating your gluteus maximus or adductor longus while walking in order to maintain a lifted inner arch of the foot. Your brain does the necessary muscle control automatically.

An analogy, and one that I use a lot, is that it's like learning to drive a car or better yet a motorcycle. Spend enough time in class learning to use the brakes and you don't have to think about how to use them, you learn to use them automatically, without thinking.

That being said, you can still notice the way that you use the brakes. And with muscle control, you can do the same thing. You can notice the sensations generated by your muscles whether the muscle activation occurs automatically or you are consciously controlling it.

More on muscle control

For more on learning muscle control and proprioception (Active muscles and connective tissue tension are what give us "proprioception" or the ability to "feel our body") check out the "take out the slack" membership program.

It includes access to all my muscle-control and proprioception courses for $40.00/month or less.

You can cancel at any time. It also comes with a 10 day money back guarantee for first time subscribers. If you aren't satisfied, for whatever reason, I'll give you your money back.

Find out more using the link below:

Take out the slack membership

Published: 2020 07 04

Updated: 2021 02 11