Outside of the context of exercise or movement, balance is pretty simple to describe. With no other forces other than gravity, an object is in balance when its center of gravity is over its foundation.

Alternatively, an object is in balance when its foundation is kept under its center of gravity.

If you are standing on one foot, you have to keep your center of gravity over that foot to stay balanced. Assuming that whatever you are standing on isn't moving, and there is no wind (externally or internally generated), then the only force acting on your relationship with the earth is gravity.

And so another way to think of balance is: that it is the state in which your center of gravity and your point of contact with the earth are in line with the force of gravity.

When cornering while riding a motorcycle, forces are generate by the act of cornering. If you add together this force and the force of gravity, then the combined resultant force is what you have to align with in order to stay balanced.

And that's why a motorcyclist has to lean their body, their bike, or both while cornering.

When riding a motorbike, it isn't the rider's center of gravity that is important. Rather, it is the combined center of gravity of both the rider and the bike that matters. This is what has to be aligned with the bike's foundation and the combined resultant force for balance.

And so a more general way to think of balance is that it is when the shared center of gravity and the point of contact with the earth lines up with the summed force that is acting on the relationship.

Now lets imagine an ideal person, one who is functionally perfect enough that they can sense where their center of gravity is with respect to their foundation.

They can feel when it is shifting with respect to their foundation and have the ability to correct for this shift so that they can keep their center and their foundation in line with the resultant of all forces acting on them.

And they can do this is any position or orientation using any part of their body (that is sensible and controllable and so discounting male genitalia, large breasts (whether male or female), hair etc.) as their foundation.

- Standing on one foot, anytime they feel their center shift relative to their foundation they counter-act that shift to stay balanced. Supporting their body on two hands or one, they can do the same thing.

- Skating, they have good enough control that they can keep their center over the blade of one skate. Better yet, they can shift their center to the inside of their gliding skate so that they actually fall towards their unsupported side. They then catch the fall by moving their other leg under their center. In this case the inbalance is a means of providing propulsion.

- Walking a slack line they can stay balanced even as the line shifts.

- Even running they have enough awareness of their center that they can adjust it relative to their landing foot so that their center is over their foot when it lands. Then, no sooner have they landed one foot than their center is ahead of that foot and they are falling forwards, using the fall to help propel them forwards, catching themself on the other foot so that they continually propel themselves forward.

Now this "idealized" human could be any one of us assuming we haven't any problems with sensitivity and control. It could be any one of us if we take the time to learn to feel (and control) our body. Then the idea of balance can be applied generally across a wide variety of activities.

The question is, what if our ability to sense and control our body is less than ideal? How do we work towards this ideal?

The simple answer is isolation.

Using isolation exercises to improve stability, awareness and control of our body

Part of learning to feel and control our body is via isolation exercises. The purpose of these exercises is to improve awareness and control of the part being isolated so that we can be have control of and be aware of that part in integrated activities, without having to think about how to feel and control that part.

Learn to feel and control the parts of the body and you can use that ability in any activity and in any type of balance.

Something to be aware of when learning balance is that even with isolation exercises, balance is more difficult the further our center of gravity is from the ground and the more joints (i.e. wrists, elbows, shoulders, shoulder girdle, ribcage, waist etc.) that we have to stabilize and control between our center and the ground.

I've practiced handstand and gotten reasonably good at it, but haven't practiced lately and as a result am no longer that good at it. I don't have enough body control while upside down. Plus I'm scared of falling.

But doesn't that prove the point that balance is activity specific?

I'll say no, because the feeling of balance in handstand is the same as when balancing on one foot. And it's also the same when doing a headstand.

One important point about handstand is that our center of gravity is higher in that pose, and we have to control more joints in between our center and the ground.

Standing upright, our center of gravity is more or less within the bowl of our pelvis. Thus, to balance on one foot, for example, we only need a reasonable amount of control of our foot and ankle, knee and hip joint (and possibly the SI joint).

In headstand, we can cup our head with our hands and brace our neck using our arms. If we have a stable base, then the main set of joints between the ground and our center of gravity is our ribcage and waist.

In handstand however, not only is our center of gravity higher, we have a much smaller foundation. And we have to stabilize and control our wrists, elbows, shoulders, and spine.

Mountain pose

Headstand

Handstand

My control is less than ideal in handstand and that gives me problems. That being said, I can balance on my hands easily in crow pose and other arm balances because my center of gravity is lower in those poses. In addition, arm balances offer the extra advantage where by one or both legs presses against an arm.

Stability and control thus tends to be easier in these types of poses.

Because my center is lower in these arm balancing poses, I can use the same awareness and control that I use when balancing on one foot. The feeling (of pressure) is the same. And that is something that can be felt and controlled in any balance pose.

What to improve to make balancing in handstand easier

So what would I need to do to improve my handstand? I'd suggest that it is developing the necessary stability and control, in particular of my wrists/forearms, elbows and shoulders, shoulder girdle, ribcage and waist.

With all of that, handstand is simply the practice of keeping ones center over the hands.

The point here then, is that with our body, it's not so much balance that is activity specific, it is stability and control.

But even that doesn't have to be activity specific.

Using any activity as a test for problems in stability and control

It could be helpful to view any activity as simply a test that uncovers a lack of stability and control that can then be worked on, first with isolation exercises, then with scaled integration.

The problematic activity, and others, can then be used as tests to see if the necessary stability and control has been arrived at.

I should point out here that stability, control and the ability to sense or "feel" our own body are all inter-related.

The central driving elements our muscles. They create the forces that move our body, stabilize it and allow us to feel it.

Connective tissue and joint capsules direct and transmit the forces that are generated by our muscle

A lot of the isolation exercises that I use tend to focus on improving stability and control of the part that is isolated.

In my book Balance Basics, I make a distinction between two types of foundation, multipoint and single point. With multipoint you can use your foundation to help you balance. A good example is bound headstand.

In this inverted pose you have your elbows and clasped hands forming a triangle with the crown of the head within that triangle.

Choosing whatever ratio of pressure you want between crown and elbows, if there is any shift in this ratio (say your elbows start to suffer an increase in pressure) then one way you can respond is by using your foundation to counter that change. If you feel elbow pressure increasing then you push your elbows down with greater force to shift your center in the opposite direction.

An important point is not to use too much pressure lest you push yourself too far the other way.

Note, if you want to be perfectly vertical in headstand, one option is to cock your head in such a way that your forehead is slightly closer to the floor. This will put a slight bend in your neck and that means you can make the rest of your body vertical while keeping weight reasonably even on head and elbows.

Another option is to shift your weight back till your weight is centered over the crown of your head. You won't be able to use your elbows (or your foundation) to help control your center. Headstand then becomes a single point foundation pose (because your elbows aren't bearing weight).

Note that in any version of headstand where your neck is bearing some or all of your weight, then your neck muscles need to be active.

If you get any neck discomfort while doing headstand, and you can't adjust it to eliminate the discomfort, then leave this pose out until you've developed sufficient neck strength, flexibility and awareness.

With single point foundations you can't use your foundation in the same way to help stay balance. If you want to stay balanced using a single point foundation, then you'll have to use other actions to stay balanced.

Basically, with single point balance positions, we have to move parts of our body relative to each other to stay balanced. This shifts our center of gravity relative to our body, and relative to our foundation.

One of my favorite single point balances is balancing on one knee.

A variation is the Shin Balance shown below. In shin balance, you can use your toes to help balance, which makes it a bit less of a single-point balance pose.

Shin balance (foot is touching the ground).

In knee balance only the knee contacts the floor, the foot of the supporting knee is lifted!)

Knee balance (foot is slightly lifted).

Knee balance variation

An important aspect of balancing on one knee is activating the hip, and there are specific ways to activate the hip that can make balancing on one foot or one knee easier. But more generally, part of what you can use this balance exercise for is to practice using different parts of the body to stay balanced.

Starting with the lifted leg, you can focus on moving just that leg to stay balanced while keeping your arms reasonably still. I usually don't explain it any more than that. Move the leg to stay balanced!

From there you can then use one arm to stay balanced, say the same side as the leg you are on. Then try moving the other arm to stay balanced.

This same trick can be used to practice balancing on one foot on a slack line. Focus on moving one limb to stay balanced. It can be the free leg, or it can be one arm or the other arm. It can even be the hips. In all cases, the point is to focus on using only one of these at a time. Once you get proficient using one limb, switch and use another.

Whatever limb you are using to stay balanced, it helps to relax it. If it was totally relaxed it would just hang down. However, if you relax or release excessive tension, just using enough muscular tension to keep the leg, or arm, lifted, your brain can then move the arm automatically and immediately whenever your center of gravity shifts.

It's very much like trying to balance on the back legs of a chair. I'd say the one difference when balancing on one knee or one shin is that you get a bit more feedback than when balancing on the back legs of a chair.

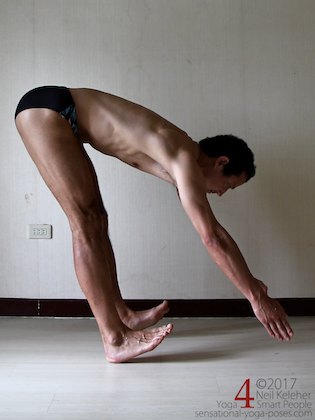

Speaking of balancing on the back legs of a chair, a pose that may be even more similiar to that is trying to balance on your heels. You can try this while standing upright.

From there you can also practice it while bent forwards. In this case you can use one or both arms (both is probably better) to stay balanced. Bent forwards you may find that you suddenly increase or decrease the bend at your hip joints to stay balanced.

The point is that you shift your center by moving one part of your body relative to another to stay balanced.

And that's something you can do in nearly any sort of balance, unless your ability to move one part relative to another is inhibited by the position you are in.

Going back to crow pose, because the center of gravity of the pose is lower, that can make it easier to balance. However, a trade of is that the legs rest on the arms. As a result, you can't move one part of the body relative to another to stay balanced.

The only thing you can do in this pose to stay balanced is to shift your body forwards or backwards relative to your hands. To do that, you can use your fingers and hands.

I mentioned running and skating earlier. In those cases, you move your feet (your foundation) under your center, or nearly under.

In these activities, and others, an awareness of center and foundation and how they relate can lead to being able to use the relationship between your center and your foundation together as a means of propulsion.

In this case, an even more general statement for balance could be: be aware of your center and foundation and the forces acting between them. Vary the relationship according to your intent.

To sum up, the better you are at feeling your body and controlling it, the easier it is to learn to balance.

With good body awareness and body control, balance does not have to be specific to any particular activity.

Now you don't have to learn to balance in the way I am suggesting here. You can just go on practicing balance in an activity specific way and still get the benefits. What then would be the point of learning balance in a non-activity specific manner? In either case, you still have to practice, whether it is balancing, or feeling and controlling your body. Why differentiate?

If, instead of just learning or practicing balance, you learn to feel your center and how it relates to your foundation, and you learn to control it, you can use that awareness, and control, for more than just better balance. You can use it for better control of your body in general.

I like to think of learning to feel your body and control it as a smarter approach because you can then apply that awareness to any activity that you do. Think of it this way. There are lots of different smart phones but the thing that is common to all of them is that that their screen acts as both an output device and an input device. And it can respond to differences in touch.

Smart phones are smart because they can feel or sense differences in touch. And they can respond in different ways based on those differences.

When you learn to feel and control your body you are improving your ability to use your body's built in sensors and actuators. And that means you can "intelligently" interact with your environment. You become a smart human. And if you constantly improve your ability to use these built in devices, it's like you are upgrading your ability to use your own hardware.

For more on upgrading your ability to use your own built in hardward check out the "Intent Driven Muscle control courses" below.

For a selection of youtube videos that focus on balance check out yoga balance videos and yoga pose inversion videos.

Intentional muscle control is about activating (or relaxing) muscles with clear intent. It's as if you are learning to lead your own body.

This isn't a dictatorial kind of leadership, at least not in the way we tend to think of dictatorship. Instead, it's the type of leadership where you partner with your body. You learn to lead it based on an understanding of what your body is currently capable of.

This type of leadership involves sensing your body (and what it is currently in contact with) so that you can direct it effectively.

Published: 2018 01 19

Updated: 2020 10 30