Obliques and Intercostals, TOC

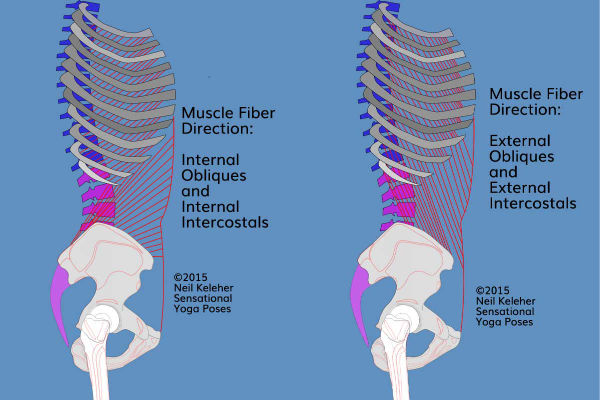

The internal layers of both sets of muscles have fibers that tend to angle forwards and upwards. Working on both sides at the same time these muscles can help "translate" or slide the ribcage rearwards relative to the pelvis.

The external layers have fibers that angle forwards and downwards. These muscles can be used to slide the ribcage forwards relative to the pelvis when both sides are used together.

The External Obliques and Intercostals and Forward Ribcage Translation

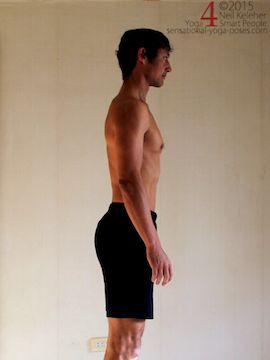

Standing upright and working from a stable pelvis, the external obliques can be used to pull the ribcage forwards relative to the pelvis.

Looking at a single set of adjacent ribs, one above the other, the external intercostals can be used to pull the upper rib forward relative to the lower one, assuming that the lower rib is "fixed" or stable.

Using the external obliques to slide the ribcage forwards

(and the external intercostals to slide upper ribs forwards relative to ribs below).

If we work downwards and imagine instead that the upper rib is the fixed rib then the external intercostal can be used to pull the lower rib rearwards relative to the upper rib. Or imagining the ribcage to be fixed in place then the external obliques can be used to slide the pelvis rearwards relative to the ribcage.

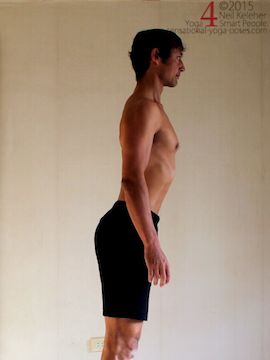

The Internal Obliques and Intercostals and Rearward Ribcage Translation

Using the Internal obliques to slide the ribcage rearwards (and using the internal intercostals to slide the upper ribs rearwards relative to the lower ribs.)

Standing or sitting upright and focusing on the internal layers of both sets of muscles, they can be used to pull the ribcage rearwards relative to the pelvis.

Meanwhile looking at a pair of adjacent ribs the internal intercostals can pull the upper rib rearwards relative to the lower rib.

Because of the opposing fiber angles, the two layers of both sets of muscles can actually oppose each other. Internal obliques can work against external obliques (on the same side) while internal intercostals can work against external intercostals.

Assuming the force produced by both sets of muscles is equal then the opposing actions of these muscles can be used to stabilize the ribs relative to each other as well as stabilize the ribs relative to the hip bones.

Focusing on the ribs and keeping the thoracic spine immobile, activating the external intercostals will create a shearing action between adjacent ribs, sliding them relative to each other. However since the spine is being kept immobile the only option is for the ribs to rotate at their connection to the spine. The result in this case is that the ribs bucket handle upwards.

While sitting or standing upright, these muscles work against the weight of the ribs and sternum. If these muscles relax then the ribs can lower due to gravity or the internal intercostals can be used to pull the ribs down.

The Intercostals as Respiratory Muscles

Practicing these movements (lifting and lowering the ribs) without allowing the spine to move you'll probably find that movement is very limited. You cannot breathe very deeply using just the intercostals.

However if you allow the spine to move, say by bending it backwards while lifting the ribs and bending it forwards while lowering the ribs, the amount of air you can move becomes much larger.

Thus the intercostals and spinal erectors, when used together, can be used effectively as muscles of respiration.

Using the intercostals, obliques and spinal erectors as respiratory muscles.

Using the Intercostals to Feel Your Ribcage

Activated intercostals can create sensation in the ribcage.

Using the external intercostals to lift the ribs causes the internal intercostals to be stretched creating a feeling of openness of expansiveness in the ribcage. While the distance between ribs probably isn't increased that much by this action it can be useful to imagine spreading the ribs or increasing the space between ribs as an aid to activating these muscles.

Likewise, using the internal intercostals to help "sink" the ribcage creates a stretch (and thus sensation) in the external obliques. Here you can focus on "contracting your ribcage" to generate sensation.

In both cases, sensation may also be generated directly within the muscles themselves. In this case, the more the muscles activate, the greater the sensation they create, particularly when said muscles are shortened and active.

In order for the spine to bend backwards or forwards (or side bend or twist) the ribs have to be able to slide relative to each other. Otherwise movements of the thoracic spine would be very limited.

While the intercostals may, via the ribs, help to move the spine, movements of the spine can also affect the intercostals.

What you may find is that you get a lot more rib movement when you allow your spine to move at the same time. But when you work at keeping your spine, particularly your thoracic spine, still, then rib movement is a lot more limited.

To that end it can be helpful to practice using the intercostals both while moving your spine and also while keeping it still.

The obliques connect the pelvis to the ribcage. This relationship could be seen as similar to that between adjacent ribs with the large difference that instead of just one vertebral joint between them there are six.

This means that the ribcage can actually be slide forwards or rearwards with respect to the pelvis by using the obliques. In either case the lumbar spine bends into a slight s-shape.

Fascicles of the External Obliques

With respect to the external obliques in particular it may be helpful to look at particular fascicles of this muscle. Some fibers attach from the ribs to the linea alba while others attach from the ribs to the front point of the hip crease. Others attach to the crest of the pelvis.

The fascicles that attach from the ribs to the front points of the hip crests (the ASIS) may be particularly important for pelvic stability when standing and flexing the hips. This group of fibers can be used to anchor the ASIS making the pelvis more stable when flexing one or both hips.

For pelvic stability during hip flexion try anchoring the point of the hip (the ASIC) using the external obliques.

The Internal Obliques

Assuming the ribs are lifted and suitably anchored, the fascicles of the internal obliques that attach to the rear portion of the iliac crest may help in anchoring the rear of the hip bones.

When twisting the spine, the internal layer of the obliques and intercostals on one side can work with the external layer on the other side.

To provide resistance (and thus sensation as well as control) the opposing muscles may also be active.

Twisting to the right, the external layer on the left side works to pull the left side of the ribcage forwards. Meanwhile, the internal layer on the right works to pull the right side of the ribcage rearwards.

Working from the bottom upwards in these twisting poses, it can help to stabilize the hip bones to give the obliques a stable foundation from which to work on the lower ribs.

This in turn gives the intercostals a foundation from which to work on the upper ribs.

Stabilizing Your Hip Bones for Deeper Twists

Whether doing a seated or a standing twist, you may find your twists are deeper if you first stabilize your hip bones. With stable hip bones your obliques, and your intercostals have a stable foundation from which to work.

Note that though the obliques cross the lumbar spine they don't attach directly to the lumber vertebrae. Likewise, though the intercostals "cross" the thoracic vertebral joints, they don't attach directly to the thoracic vertebrae. In both cases, other muscles are required to help twist the vertebrae relative to each other.

The rotators and multifidus are muscles that span vertebral joints from transverse processes of lower vertebrae to spinous processes of upper vertebrae. They can be used to turn the vertebrae relative to each other.

In the lumbar region, twisting can also be helped by the the psoas and quadratus lumborum, both of which attach to the lumbar vertebrae.

The psoas major attaches to the sides of the vertebral bodies and intervening discs.

Both the quadratus lumborum and the psoas attach to the lumbar transverse processes.

One reason for activating these additional muscles is that they can help you feel your spine, giving it sensation. They can also help to stabilize the vertebral joints as you twist your vertebrae relative to each other.

Because the spinal erectors bend the spine backwards they can be used to move the ribs away from the pelvis adding tension to the obliques. You could also think of this as "taking out the slack".

This is one way of making the abs easier to control.

Another way to take out the slack from the obliques, so that they are at optimal operating length, is to pull inwards on the belly using the transverse abdominus.

1. Transverse Abdominis relaxed.

2.Transverse Abdominis activation so that Belly is pulled in.

In a standing side bend you can activate and shorten the obliques (both internal and external) on one side. To provide resistance and sensation, the obliques on the opposing side can also activate, however they will be lengthening as opposed to shortening.

You can pull in on the transverse abdominis to help add tension to both sets of obliques on both sides of the body.

In the two side bends shown above, my focus was more on pulling in with my transverse abdominis. That being said, with the transverse abdominis engaged, you can also then focus on contracting the short side (the right side in these pictures) while at the same time creating space in the long side (the left side).

In a side bend, you can also use your intercostals to help bend the ribcage. This is something that is best done by feel, which is appropriate since your intercostals can help you to feel your ribs as well as control them.

You can also use spinal muscles to help feel and control your spine in this type of pose.

A simple way to learn to feel and control the obliques and intercostals is to twist. Try it while sitting or standing.

Turning your ribcage to the right you can focus first on the lowest set of ribs, turning them with respect to the pelvis. Then move to the next set of higher ribs and turning them with respect to the lower set of ribs.

Repeat all the way up your ribcage (there are 12 pairs of ribs in all.)

For deeper awareness focus on one side at a time. Twisting to the right focus first on the right side ribs, then keeping the twist focus on each rib in turn on the left side.

Because of their attachment to the sternum you may find the upper 7 pairs of ribs more difficult to turn than the lower 5.

Feeling Your Vertebrae While Twisting (as well as your Ribs)

An additional exercise for a more complete twist is to focus on turning your vertebrae. The lumbar spine has 5, the thoracic 12 and the cervical spine has 7.

Twisting to the right you can focus on feeling and turning vertebrae first, working from the bottom up. Then focus on your ribs to deepen the twist.

When twisting relative to your hip bones, focus on keeping your hip bones still as you twist your spine and even more so as you focus on turning your ribs.

Published: 2015 12 27

Updated: 2019 08 11