Tensioning the knee joint capsule to maintain joint integrity

For details on knee joint capsule tensioning, check out this article on maintaining knee joint integrity int the middle splits.

A related article that builds up on the ideas presented in that article is stabilizing the knee joint in middle splits.

Knee Joint Hinging

Knee Straightening Muscles

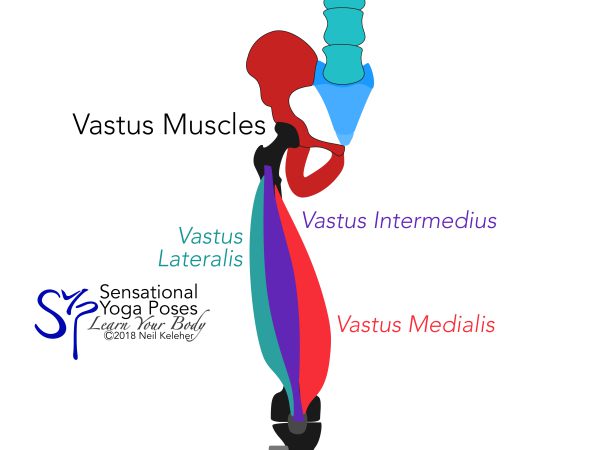

The main muscles that act to straighten the knee are the vastus muscles. These are:

- the vastus medials,

- vastus intermedius and

- vastus lateralis.

These three vastus muscles make up most of the bulk at the front of the thigh. Normally these are grouped together along with the rectus femoris as the Quadriceps! However, the rectus femoris, unlike the vastus muscles, is also a hip flexor.

In addition to straightening the knee these muscles also resist the knee being bent.

Adding tension to the long hip flexors

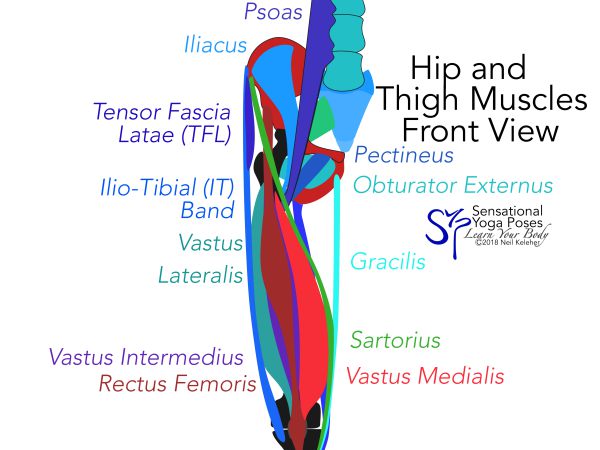

Because the vastus muscles are all relatively massive, they tend to press out against overlying muscles (in particular the long hip flexor muscleswhen active.

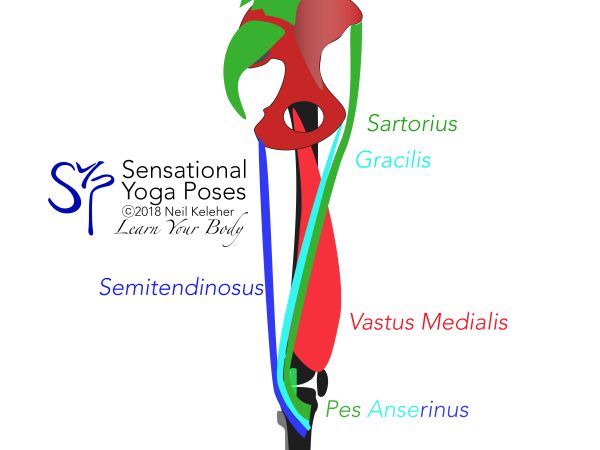

And so as well as acting to straighten the knee, these muscles may also help to remove slack from overlying muscles like the IT Band muscles (the tensor fascia latae and gluteus maximus) as well as the sartorius and gracilis, both of which attach to tibia as part of the pes anserinus.

Assuming muscles have an optimal length for effective activation

This assumes that muscles have an optimal length (or optimal length "range"). So for example, if, while standing, with the knees bent the IT Band isn't at optimal length (perhaps having too much slack), activation of the vastus lateralis helps to remove the slack so that the tensor fascia latae can activate.

Knee Bending Muscles, hamstrings and gastrocnemius

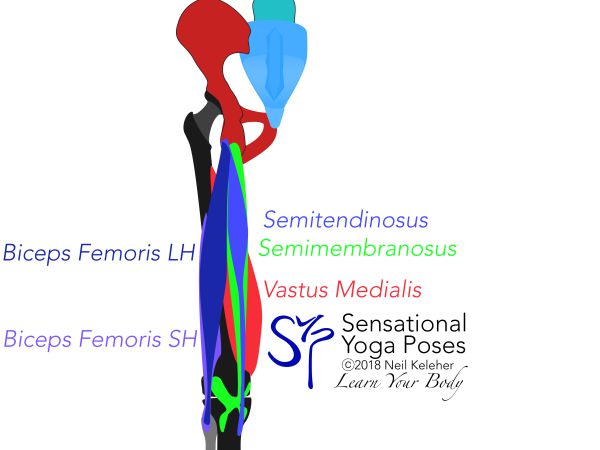

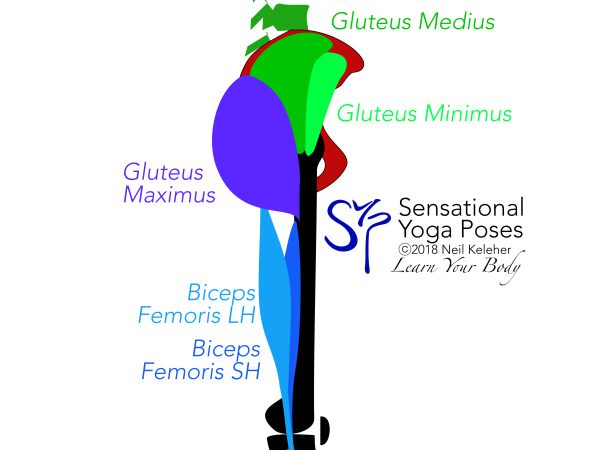

Muscles that can be used to bend the knee or resist it being straightened are the hamstring muscles. This includes the biceps femoris (both long head and short head) which attaches to the fibula, and the semimembranosus and semitendinosus, both of which attach to the inside of the tibia.

Note that the tendons of semitendinosus, gracilis and sartorius share a common connection point to the inside of the tibia called the pes anserinus.

Another muscle that can help bend the knee or resist it being straightened is the gastrocnemius, the larger of the two calf muscles. The two upper tendons of this muscle pass between the tendons of the inner and outer hamstrings before attaching the the bottom of the femur.

Stabilizing the Knee Against Hinging

To stabilize the knee against hinging the vastus muscles can be used against the calf muscles, particularly while standing. With weight pressing through the feet, the calf muscles are potentially anchored at the heel. The quadriceps can then work against the gastrocnemius to stabilize the knee joint.

The quadriceps could also work against the hamstrings to stabilize the knees against hinging. If the pelvis and hip joints are stable, then the hamstrings have a stable foundation from which to act on the knee. Assuming hip flexors are active to counter-act the hip extending action of the hamstrings, then it may be possible to activate the hamstrings against the quadriceps to stabilize the knee joint against bending or straightening.

Either of these muscle pairs (vastus against gastrocnemius or vastus against hamstrings) could be used with the knee straight, or bent in various positions.

Single Joint knee rotators

Two important posterior knee muscles for directly controlling rotation of the shin relative to the femur are the popliteus and biceps femoris short head.

Anterior knee muscles that help to control knee rotation are the vastus muscles, in particular the vastus medialis and the vastus lateralis.

For these muscles to work effectively, it can help either to stabilize the lower leg bones against rotation or to stabilize the femur against rotation. If either the femur or the lower leg bones are stabilized against rotation, then the knee rotators can stabilize or control rotation of the shin relative to the femur.

Vastus medialis Obliquus or VMO

The vastus medialis obliquus isn't necessarily a muscle in its own right. But it does bear mentioning in its own right. It's the bottom portion of the vastus medialis muscle and it's notable because it attaches to the tendon of the adductor magnus muscle. The rest of the vastus medialis attaches directly to the femur.

Adductor magnus long head is an internal hip rotator. It can work against the gluteus maximus (and with other hip rotators) to help stabilize the femur against rotation at the hip joint. It's notable in the context of knee rotation stability because not only does its tendon serve as an origin for the VMO, but because it attaches to the bottom of the femur.

The other single joint hip rotators attach close to the hip joint. The adductor magnus long head is the only single joint hip rotator that attaches close to the knee joint at the bottom of the femur.

It's point of attachment to the bottom of the femur is more or less on the opposite side of the bottom of the femur from the popliteus.

What happens when the adductor magnus long head activates against an external rotator like the gluteus maximus? It exerts a rearwards force on the inside of the bottom of the femur thus causing the outside of the bottom of the femur to rotate forwards. This can help to anchor the popliteus which can then work to internally rotate the knee. Meanwhile, VMO can activate from the tensioned tendon of the adductor magnus long head to also internally rotate the knee while at the same time helping to oppose the knee flexing or bending action of the popliteus.

Biceps femoris short head can activate to externally rotate the knee along with vastus lateralis.

For a simple set of exercises for how to activate the adductor magnus and subsequently the vastus medialis, check out the Learning to activate adductor magnus long head and VMO course.

Dual joint knee rotators

For extra stability against knee rotation, multi joint muscles that work on the knee and the hip can be called into play.

Dual joint knee rotators that work on the hip and the knee can be divided into two groups. The outer thigh knee rotators include the tensor fascia latae and superficial gluteus maximus. In addition there is the biceps femoris long head. Inner thigh knee rotators include sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus.

If the lower legs are stabilized at the foot against rotation, then these knee rotators may not act so much as knee rotators. Instead they can act to control the hip bone.

Outer thigh knee rotators

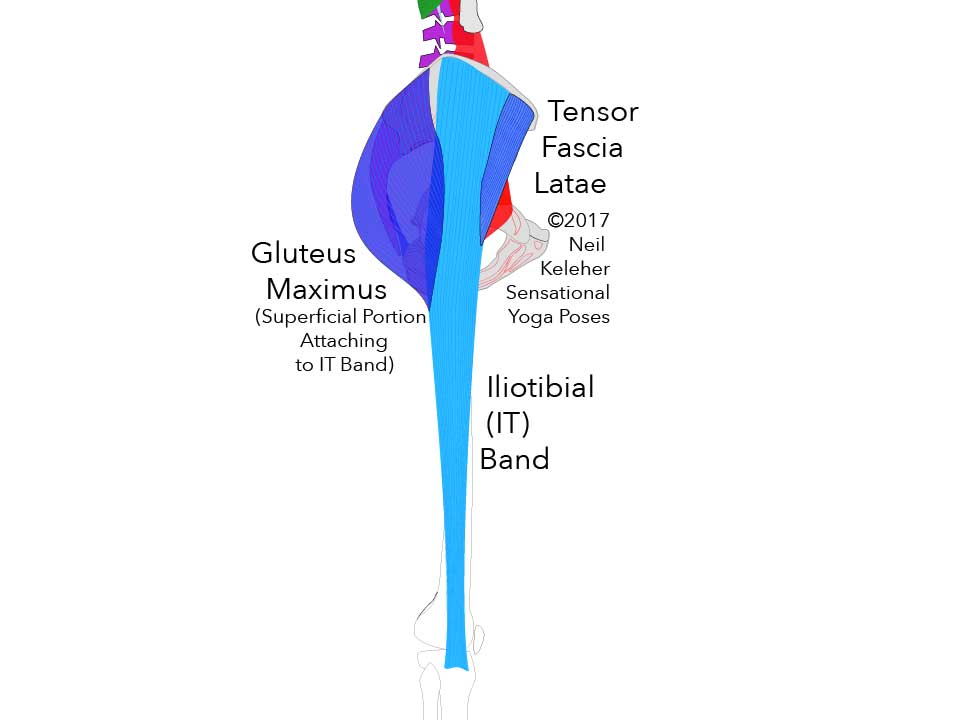

The first group of outer thigh knee rotators includes the IT band and the muscles that work on it, the tensor fascia latae and the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus.

The IT band passes over the vastus lateralis to attach to the top of the tibia in front of the tibia.

- The tensor fascia latae attaches to the front edge of the IT band and can be used to rotate the shin internally if the knee is straight.

- The gluteus maximus attaches to the back edge of the IT band and can be used to rotate the shin externally.

- If the knee is bent (and the foot is lifted off of the floor) then both muscles can be used to rotate the knee externally.

As mentioned, to remove slack from these muscles so that they can more effectively control (or help control) shin rotation, the vastus lateralis may co-activate.

Another thigh muscle that can be used to rotate the knee is the biceps femoris long head. This muscle, like the biceps femoris short head, attaches to the top of the fibula.

Using vastus lateralis as an intermediary

Both the long head and the short head of the biceps femoris are located adjacent to the vastus lateralis muscle. If the vastus lateralis is activated, and it's sufficiently bulky enough, it can push the biceps femoris inwards, perhaps varying the angle of pull of that muscle on the fibula, or, again, helping to give it operating length so that it can operate effectively.

The biceps femoris long head can be used to externally rotate the fibula.

Ideally the fibula and tibia rotate together, and so it can be important to synchronize any rotation forces that act on the fibula and tibia. And that may be where the vastus lateralis is useful as an intermediary.

Inner Thigh Shin Rotators

Three muscles that attach to the inside of the tibia to form the pes anserinus are the sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus.

With the knee bent and foot lifted, these muscles can all be used to help rotate the knee inwards.

If the knee is stabilized against bending, it should be noted that the sartorius can help externally rotate the thigh at the hip joint while at the same time internally rotating the shin at the knee joint.

Stabilizing the Shin Against Rotation at the Knee Joint

If the knee is bent, the pes anserinus muscles can work against the IT band muscles to stabilize the shin against rotation.

If the knee is straight then the tensor fascia latae can work against the gluteus maximus to prevent rotation.

Another possibility with the knee straight is that the sartorius could work against either the gracilis or the semitendinosus to prevent shin rotation.

As mentioned, the hamstrings can also be used to help control knee rotation whether the knee is straight or bent. Since the hamstrings also work to bend the knee, the vastus muscles would also have to be active to help control changes in knee bend.

Controlling the Knee

Part of controlling the knee can involve stabilizing either the femur or the lower leg bones.

The idea is to give muscles that act across the knee joint at least one stable or fixed end point from which to act.

To stabilize the femur against rotation, two important muscles are the adductor magnus long head and gluteus minimus. Both can cause internal rotation or at the very least resist external rotation of the thigh relative to the pelvis.

So that these muscles have an opposing force to work against, an external rotator like the deep fibers of the gluteus maximus, the obturator internus and the quadratus femoris are also important.

If the femur is stabilized against rotation at the hip joint, using internal hip rotators against the external hip rotators, the hip bone can then act as an anchor for the shin rotation muscles to effectively control the lower leg bones.

By the same token, if the shin is stabilized against rotation via muscles of the foot and ankle, then the long hip muscles have an anchor from which to work on the hip bone.

Muscles that attach between the lower leg and femur, for example, the previously mentioned popliteus and short head of the biceps femoris, also have an anchor from which to act on the femur.

Alternative Strategy for Knee Control

Since some of the shin rotator muscles attach to the hip bone, another way to make the knee joints more controllable (and/or more stable) is to anchor the hip bones via the abs. For example, creating an upward pull on the ASICs via the external obliques can give sartorius, rectus femoris and tensor fascia latae an anchor point from which to effectively control the lower leg bones.

More on knee joint stability

For more on knee joint stability check out:

Published: 2012 08 03

Updated: 2021 02 11