Do the Sartorius and Gluteus Maximus Relate?

It wasn't until recently that I started running again (more like hobble for a bit then walk for a bit) that I seemed to have gotten to the root of the problem and gotten closer to the optimal algorithms for that side of my leg while running. In the process one of the things that I uncovered was a seeming link between the portion of the gluteus maximus that attaches to the IT band and the sartorius.

The Sartorius, A Long Thigh Muscle

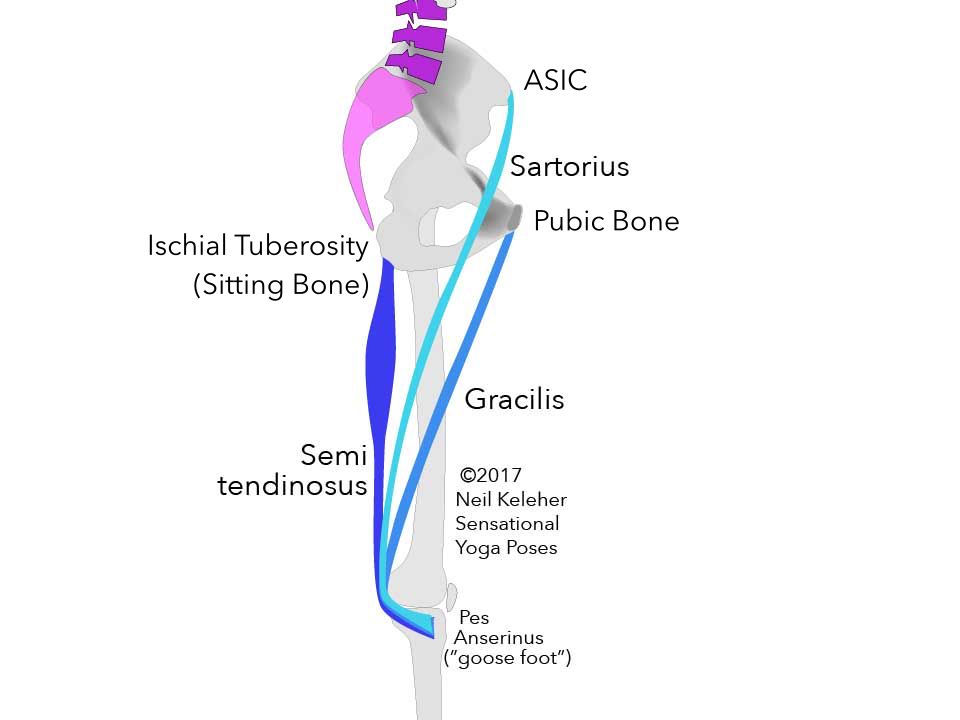

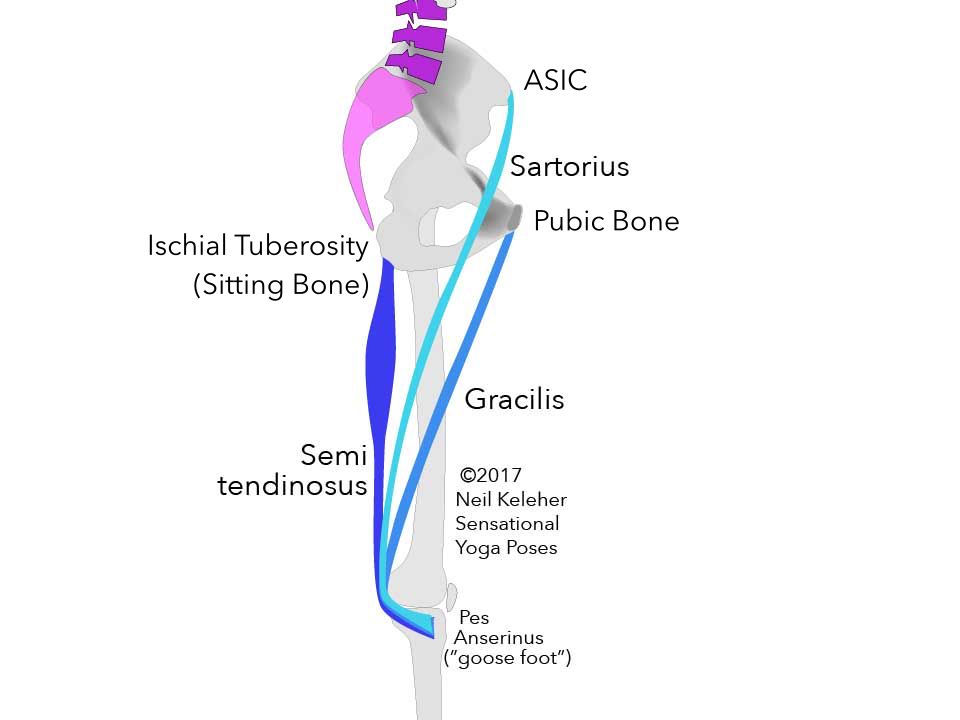

The sartorius could be thought of as one of the long thigh muscles.

At its uppermost end it attaches to the front point of the hip crest (the ASIC or Anterior Superior Iliac Spine).

Inner view of thigh showing goose foot or pes anserinus muscles: sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus.

From there is runs downwards and rearwards along the inside of the thigh, angling behind the bulk of the rectus femoris and vastus medialis before bending forwards just below the bump of the knee to attach to the inside surface of the tibia along with two other "long thigh muscles", the gracilis and the semitendinosus.

At this shared insertion these three muscle tendons form a goose foot shaped structure called the pes anserinus (which is latin for goose foot).

Corner Points of the Pelvis

These three muscles all attach to prominent "corner points" of the pelvis.

Where the sartorius attaches to the ASIC,

the gracilis attaches to the pubic symphysis (or pubic bone) while

the semitendinosus attaches to the ischial tuberosity or sitting bone (the bones on either side of and just rearwards of the anus that you can feel when sitting down.)

Where the three pes anserinus muscles run separate for most of their length before joining at the tibia, the corresponding structure that runs along the outside of the thigh, the IT band, is joined for most of its length.

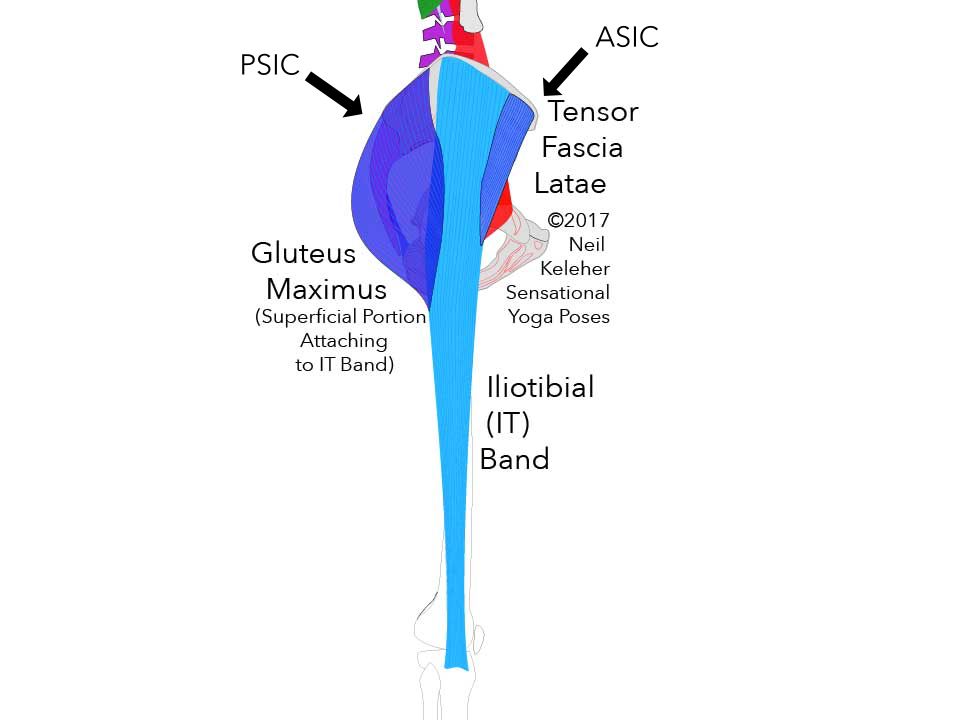

The IT Band

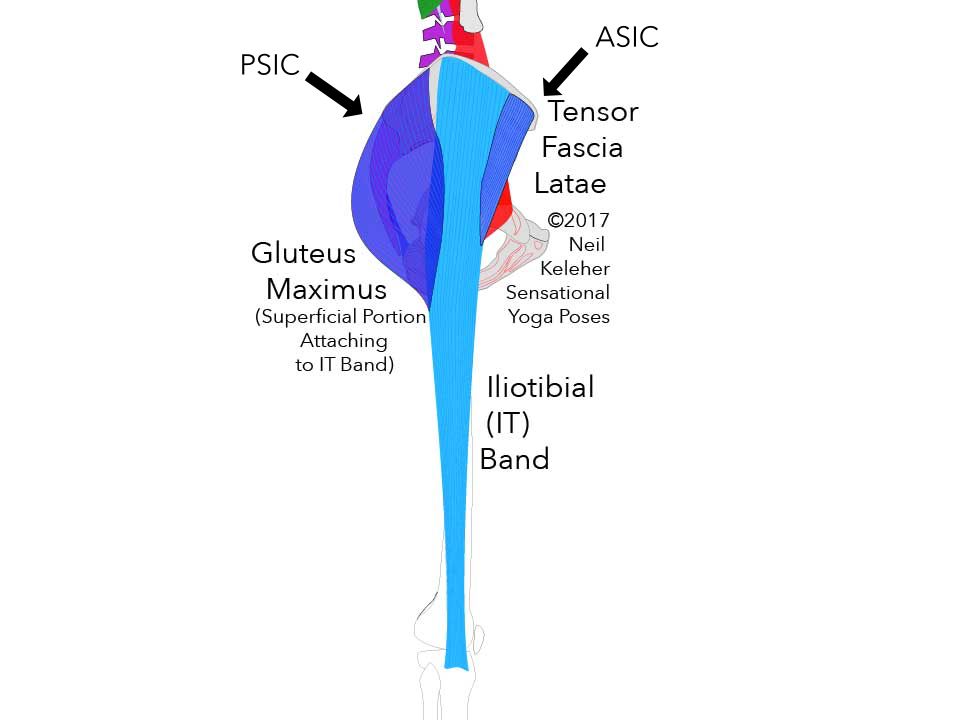

The IT band runs down the outside of the hip and thigh from the iliac crest to the top of the tibia.

Two muscles that attach to it are the tensor fascia latae and the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus.

One way to model or think of the IT band is as two separate tendons that are joined along their length. The front tendon is worked on by the tensor fascia latae. The rear tendon is worked on by the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus.

These muscles also attach to prominent corner points of the pelvis.

Like the sartorius, the tensor fascia latae attaches to the ASICs and from there passes downwards and rearwards before attaching to the front edge of the IT band near the greater trochanter, the "bump" of the thigh bone that you can feel half a hand span below the crest of the hip.

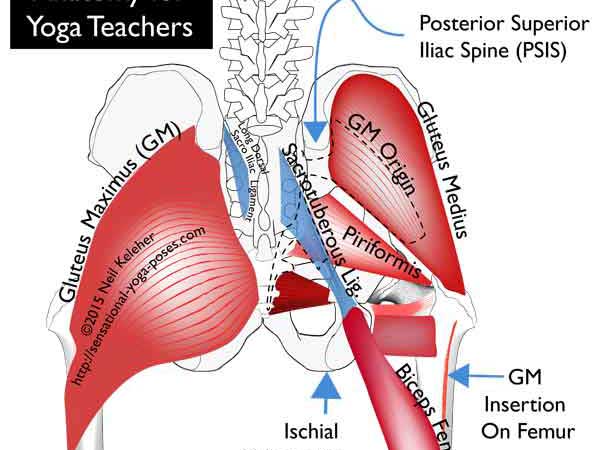

The gluteus maximus attaches to the PSIC (the posterior superior iliac crest or the rear part of the iliac crest) and runs forwards and downwards to attach to the rear edge of the IT Band.

Outer view of the thigh showing the IT band, tensor fascia latae and gluteus maximus muscles.

Trying to match strides while running so that my left knee and hip felt like my right, at some point I experienced some slight releases in my knee, like material tearing.

Connective Tissue Scaffolding

One thing that may happen when the brain uses other algorithms to run the body after an injury is that temporary connective tissue structures build up to support the new movement patterns. These could be thought of as scaffolding. Ideally they are temporary in nature.

My thoughts (and hopes) where that these little tears were just indications that connective tissue scaffolding was being disassembled.

Bear in mind, it's been 18 years or so since the accident, so that should have been more than enough time for any damaged tissues to heal.

Knee Tightness After Running

I carried on running and my knee felt fine. However, later on, after a stretch and a relaxation the back of my knee started to tighten up.

This has been pretty much the case for most of my runs and I've found that by the next morning the tension usually released. When it didn't, I sometimes found that playing with heel and or outer foot stabilization sometimes helped.

A Tearing Sensation at the Front of the Knee

Running again the next day, or I should say jogging for short distances then walking for longer distances before jogging again, I experienced a different sort of slight release in the knee.

This series of light tears (or what felt like it) was towards the front inside of my knee below the knee cap. So I stopped to walk.

There's not much in the way of muscle near the bottom of the front face of the knee. The only muscle I could think of that was close and that might be remotely helpful was the pes anserinus muscles (Sartorius, gracilis, semitendinosus).

Activating the Pes Anserinus Muscles (Sartorius in Particular)

I activated or tried to activate the pes anserinus muscles by creating a forwards and upwards pull on the inside of the top of the tibia. That seemed to help.

Because one of these three muscles, the sartorius, attaches to the ASIC, I thought it might be worth creating an upwards pull on my ASICs. The idea of this was to anchor the upper end of the sartorius so that it was then easier to create an upwards pull at the pes anserinus (at the inside of the top of the tibia).

That helped a little for the current run. And that was more or less what happened during the course of each subsequent run. What worked one day wouldn't necessarily work the next day so that I had to constantly explore muscle control options.

Generally while I was walking I would try various muscle control techiques to see what worked or helped while walking. Then I'd try it while jogging.

Whenever I lost technique or felt my knee beginning to give way then I began walking again.

Creating Some External Rotation with the Gluteus Maximus

Continuing with another bout of running I got the sense that my inner knee needed some stress relief. It felt like I needed to rotate my thigh and shin outwards slightly.

What felt "right" was using my gluteus maximus to create the outward rotation. At the time it felt like I was mainly using the superficial portion of this muscle to create the rotation. This is the portion that attaches to the tibia via the IT band.

What I later found was that the deeper fibers of that muscle where also activating, particularly at heel strike. But because the muscle had a slight stretch at the moment of activation it was harder to feel the activation.

Varying the Amount of Leg Rotation

While the muscles that I used to create the external rotation was important, what was also important was the amount of rotation.

If you try the shin rotation exercises in shin rotations and heel stability you may notice that while rotating your shins outwards you may find more tension along the outside of the knee along with greater pressure along the outer edge of the foot.

While rotating your shins inwards you may find more tension along the inner knee and greater pressure along the inner edge of the foot.

Then there's a middle or neutral position where the inside and outside of both the knee and the foot feel roughly equal in tension and pressure.

While running I found that having my shin just slightly externally rotated during heel strike felt most comfortable on my knee.

The amount of external rotation used seemed to naturally cause me to land on the outside of my heel and also seemed to take some pressure off of my inner knee, placing it more on the outside of the knee.

Note that at this point I was still also aware of using my sartorius.

Problems with the Gluteus Maximus In Pigeon Pose

Now I've had trouble with my left side gluteus maximus muscle for a while.

Doing Pigeon Pose Glute Stretch with the shoulder on my front foot side pressing towards my front foot, when pressing the edge of the foot strongly into the floor with right leg forwards I can feel the gluteus maximus activating. With my left leg forward, not so much.

One of the other sensations that I experienced while comparing my left and right legs in pigeon pose was that I could "feel" my right hip bone, my good side, particularly at the ASIC and PSIC. My left side, not so much.

This seeming failure of my gluteus maximus to function also had a noticeable affect when I first experimented with a heel strike while barefoot running .

Barefoot Running with a Heel Strike

I experimented briefly withbarefoot heel strike running about a year ago.

Walking I found I didn't have any problem with a barefoot heel strike. When running I found that my left knee tended to cave inwards. And it seemed to be due to a failure of my gluteus maximus.

It would function if I payed attention to alignment, but I couldn't keep it up for long. But when I could maintain it, using a heel strike while running barefoot felt fine.

When the knee is straight the shin cannot rotate relative to the thigh.

Because of the way the sartorius passes behind the knee before attaching to the inside of the top of the tibia, when the knee is straight the sartorius creates a forward pull on the back of the inside of the knee causing external rotation.

When the knee is bent the sartorius, along with the other pes anserinus muscles, can rotate the shin inwards relative to the thigh.

Now in my more recent bout of running I find that I can run without my knee caving in.

Adding the two experiences together it seemed that the gluteus maximus (particularly the part attaching to the tibia) needed the sartorius to give it something to work against.

It may also have needed a stabilized heel, something else that I was trying to create while running.

The Sartorius and Preventing Inner Knee Gapping

After some more runs, the feeling I had, was that the inside of my knee was "gapping" or hinging open slightly and adding tension to the sartorius seemed to help to prevent this.

This was provided I had enough external rotation and that I didn't lose this external rotation during the heel strike.

When the knee is slightly bent during the heel strike portion of the stride while running or (as in my case, jogging), the sartorius can create an internal rotation force on the tibia, assuming the hip bone is stable and assuming the knee is only slightly bent.

To prevent gapping, the sartorius may also create an upwards pull on the inside of the top of the tibia helping to prevent the inside of the tibia from spreading apart from the inside of the femur.

For the sartorius to be able to carry out this function, the shin needs to have an external rotation force acting on it to counteract the internal rotation that the sartorius tends to create.

While lying in bed I found that my knee seemed to become lose in certain positions, likewise while sitting. Here again it felt like the inside of the knee was the part that was lose.

Straightening the problem knee while sitting so that my foot lifted, I then turned my leg externally so that the inside of the knee was turned uppermost. I then tried to activate the sartorius by creating a tightening force on the inside of the knee. Basically, I tried pulling the inside of the top of the tibia towards the groins.

Comparing sides I found that the good side naturally had this pull as if the sartorius (and perhaps gracilis) where activating automatically. I just needed to train the other side to do the same.

The Sartorius and Taking Out the Slack

I mentioned earlier that I tried anchoring the upper end of the sartorius, and form my earlier runs that helped. Later on I found that I also needed to play with "taking out the slack" from the sartorius. To do this I played with activating the inner thigh muscles (the adductors) as well as the vastus medials muscle.

For the IT Band, taking out the slack is relatively simple. Activate the vastus lateralis since the IT band runs over this lateral thigh muscle.

For the rectus femoris, slack can be taken out by activating the vastus intermedius (over which it runs.)

With the sartorius, the answer might not be so simple.

Some slack may be removed from the sartorius by activation of the vastus medialis. However, it seems that it is more prone to activation if the inner thigh as a whole is relatively active. And so to take out the slack from the sartorius it may help to activate the adductors as well as the vastus medialis muscle.

For me it still helped to use gluteus maximus to externally rotate the thigh just enough. Then I found that inflating the inner thigh also helped.

Anchoring the IT Band

But of course, on the days that followed I still had problems.

Going even deeper, I knew that activating the tibialis anterior can be helpful with alleviating IT band knee pain, particularly while squatting. I then learned (or re-learned) that the peroneus longus muscle also has IT band connections.

Where the tibialis anterior attaches more to the front fibers of the IT band (which relates to the tensor fascia latae) the peroneus longus attaches more to the rear fibers (which relate to the gluteus maximus).

And so I played with activating both the tibialis anterior and the peroneus longus to anchor my IT band to see if that helped my superficial gluteus maximus.

Note that both of these muscles can be activate by the simple expedient of stabilizing the heel. (For some tips on heel stabilization read Shin rotations and Heel Stability)

Playing with peroneus longus and tibialis anterior activation also helped when dealing with after run knee tightness.

Heel Striking with a Stabilized Heel

My jogging stride is, currently, fairly short, and I found that stabilizing the heel on heel strike is quite helpful. No pain, no "tearing" and relatively comfortable running.

An interesting thing is that about a year ago I finally read about how the IT band may be designed as an energy storage device, basically an elastic, for more efficient running.

Storing Elastic Energy In the IT Band

For a regular elastic band to store energy you have to pull create two fixed endpoints.

By stiffening the heel prior to impact, could actually help to anchor the bottom end of the IT band, creating one fixed endpoint. Body weight pressing down via the lumbar spine into the back of the pelvis could help to create the other fixed end point.

So in my recent runs I experimented with barefoot heel strike jogging for short distances. It actually felt quite comfortable. Putting shoes back on I worked at creating a solid heel strike despite my relatively soft trainers.

If you've ever watched pole vaulters or high jumpers, my running felt like the way their run ups looked.

Each stride I tried to come down on a stiffened heel.

I still wasn't running super fast or going long distances, but my stride felt noticeably easier and my running lighter.

A year ago when I tried this technique my knee tended to cave inwards, and even then I realized the problem was with the superficial glutes. Maybe sartorius needed to be active so that my glutes could work.

Heel Stiff, Forefoot Relaxed

Now while I stiffen my heel during heel strike, currently it feels better to keep my forefoot relatively relaxed, or rather to do it's own thing during heel strike. But, now that my sartorius and glute max are working together I have began to play with varying shin rotation during or after heel strike to see how best to utilize my forefoot. A slight inwards rotation seems to allow me to press off strongly with the inner edge of my forefoot at the tail end of my stride.

Shin to Thigh Rotation

On a later run I played with shin rotation relative to the thigh.

I found that externally rotating my shin relative to my foot by using my peroneus longus muscle first and then varying the amount of rotation of my thigh relative to my pelvis (I tried a little bit more outward rotation then a little bit more inward rotation) seemed to help. Later on I focused on simply stiffening the outer edge of my foot and heel.

Heel and Outer Foot Stiff

Note that the heel bone (calcaneus) could be thought of as part of the outer foot since the outer two toes (the littlest ones) all end up at the heel bone while the inner three toes (the biggest ones) terminate at the ankle bone (talus).

One problem I had with this technique is that running up hill it caused some snapping sounds to emanate from my knee.

It wasn't until after a couple of runs that I realized it happened while I was running up hill. Modifying my foot action I found that stiffening just the heel and relaxing my forefoot seemed to not cause any problems while running up hill.

If experimenting with stiffening the outer foot (or "externally rotating the shin relative to the foot") be aware that you may have to switch this activation off when going up hill.

I did try increasing the forward tilt of my pelvis while running down hill in the spirt of "varying techniques to suit the terrain." Following the same line of thought, the pelvis could be tilted backwards while running up hill.

The reason for this is to maintain length in the sartorius and other hip flexors.

What I then found, running up hill with the pelvis tilted backwards, was that it helped to land with my foot ahead of my center. Running on flat land I could land my heel beneath or even slightly behind my center of gravity.

Landing with the foot ahead of my center of gravity could allow me to still land with a stiff heel and outer foot.

Tai Ji Knee Collapse Problems

Trying a few movements from Tai Ji I found that one transition gave my knee some problems. And the problem seemed to relate to the problems I've been having while running.

I found that my knee tended to cave in when doing a transition from a Warrior 1 like stance in one direction, changing direction 180 degrees so that the problem leg was forwards with knee bent and from there standing on the front leg with knee still bent.

The problem occurred on the bent leg while trying to reach with the empty leg while keeping my upper body relatively upright.

During the sequence of posture changes I wasn't preparing my leg for bearing all of my weight.

I found that I had to set up my hip and knee prior to bending the knee and prior to shifting weight to it.

Preparing the Knee for Janu Sirsasana

I'd experienced a similiar solution doing the seated pose janu sirsasana (shown below right).

Bending forwards with my problem knee bent, it felt uncomfortable, even if I did try "activating" the knee (making it feel strong!).

So I pointed the knee upwards first (still bent) so that I was in a posture like marichyasana A (below left). I activated the knee in this position, then kept it active as I moved the knee out to the side for janu sirsasana.

I found now that my knee was actually comfortable when I bent forwards.

Janu Sirsasana A with torso upright

Marichyasana A with torso upright.

While walking I tried to get my leg ready (in particular the knee and hip) just before each heel impact and that felt tentatively quite good.

I did this by creating just enough tension in my hip and knee to give both joints sensation.

Feeling inspired I also tried to stabilize my hip joint (a sort of "squeezing" of the hip joint) prior to heel strike and that also felt good.

But as with most of my problems, that was only part of the solution.

More Tai Ji Knee Collapse Problems

Trying Tai Ji the next day I found I still had a collapsing knee. Comparing sides my right hip (the good one) felt different than the left hip.

A long time ago I used to challenge myself standing up from a forward bend on one leg. (It's challenging if you keep pulling the lifted leg forwards).

One technique for making it easier was to spread the sitting bone of the supporting leg.

Trying to stand up while keeping the lifted leg pulled forwards can be challenging for the standing leg.

Activating Obturator Internus

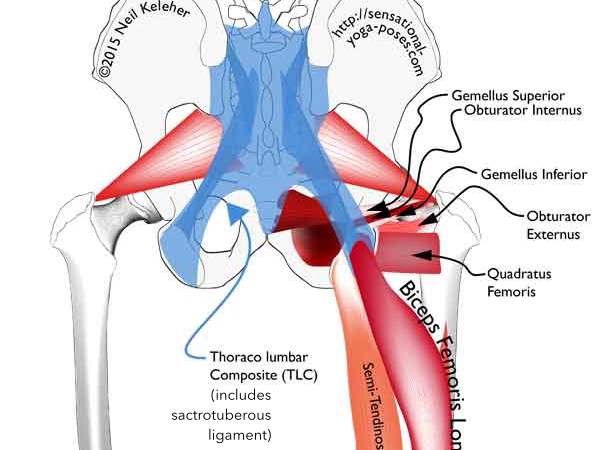

Spreading the sitting bones (both of them or one) activates the Obturator Internus which in the process adds tension to the sacrotuberous ligament..

The sacrotuberous ligament attaches between the sacrum and the ischial spine, just above the sitting bone. Both the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings (in particular the long head of the biceps femorous) attach to it.

Spreading both sitting bones, with weight on both feet, creates an outwards pull on both sitting bones. It can also cause the pelvis to tilt forwards. This action pulls the ischial tuberosities away from the sacrum which in the process adds tension to the sacrotuberous ligaments. Because of the way that the SI joints are designed to move, this causes the ASICs to move inwards.

Spreading one sitting bone, in particular while on one leg, the work is in preventing a change in the left-to-right tilt of the pelvis.

Standing on the left leg, to add tension to the left sacrotuberous ligament, I had to work to prevent the right side of the pelvis from dropping while spreading the left sitting bone.

Why Adding Tension to the Sacrotuberous Ligament can be Helpful

Adding tension to the sacrotuberous ligaments can provide an anchor for the fibers of the gluteus maximus and hamstrings (particularly the biceps femoris long head) that attach to it.

And actually, when got the idea of spreading the sitting bone while doing Tai Ji my first thought was that it was a way of activating the outer hamstrings. At the time I'd forgotten about the obturator internus and the sacrotuberous ligament.

Both the long head of the biceps femoris (as well as the short head) attach to the top of the fibula and have connections with the peroneus longus (just like the fibers of the IT Band).

Giving the sacrotuberous ligament extra tension gives fibers of both of these muscles a fixed anchor point meaning that either can easily activate when needed.

In a more upright position with the knee less severely bent, as in the heel strike phase while running or jogging or even walking, either set of muscles could activate to create an external rotation force at the top of the fibula.

At any rate, spreading the sitting bone just before the heel strike while running felt good.

Adjusting Alignment for Obturator Internus Activation

To use obturator internus to create an outwards pull on the sitting bone while running I had to make some adjustments.

The obturator internus creates an external rotation force on the femur. But it needs enough length to do this and so to "spread the sitting bone" it helps to have the femur pointing forwards with neutral rotation.

Compared to when I first started this running experiment this meant that I was actually internally rotating my thigh slightly.

As with all of the previous experiments, I went by feel to determine the amount of thigh rotation that I needed.

The goal of adjusting thigh rotation was to find a position where my knee (and the rest of my body) felt comfortable.

Making Muscle Control Habitual

The overal goal of all of the above experimentation was to run without inner knee pain. Or any knee pain for that matter. As of now I've been going for runs for about 3 weeks. I'm not getting as much "back of the knee" soreness the next day. And now I don't need as much of a walking warm up prior to running.

The necessary muscle control is becoming habitual.

Generally what I've found with "muscle control" is that after a little bit of practice whatever muscle control actions I've been working on become automatic or habitual. So now I don't have to consciously focus on externally or internally rotating my thigh. I don't have to work at creating an upwards pull at the bottom of the sartorius. My brain knows what needs to be done and takes care of it.

I do have to be aware though.

It's similiar to the overal awareness you can have when you've been driving for awhile. You use the brakes when you need to without thinking about how to do it.

I do still find that if my mind wonders, or I turn my head to look behind me, that can sometimes cause minor set backs.

But hopefully, the more I run, the better I'll get (or the better my brain will get) at handling these small perturbations without any negative side affects.

Noting the path of my leg swing and a displaced pelvis

update: 2021 08 19

It's now about two years later. I started getting what I would label as excessive tension in the biceps femoris short head, basically one of the outer hamstring muscles on my left leg.

One of the problems I noticed is the way that I swing my left leg while walking. On the forward swing, I tend to swing my foot more or less straight ahead. Meanwhile, my right foot seems to swing inwards.

I played with varying my leg swing, swinging the leg inwards so that my heels crossed. And from there I also played with giving my leg some external rotation. How much rotation? I found that with just the right amount of rotation (and just the right amount of adduction), I could feel tension in both my sartorius and gracilis.

Of course, I practiced this fix, and the next day it no longer seemed to help. What I then realized is that as a result of previous knee injuries, or simply a bad movement pattern, I tended to walk, and even stand, with my pelvis slightly to the right, relative to my feet. It may have been a result of trying to reduce weight on my left knee as a result of an injury, or as I mentioned, it was simply a habit I developed.

So then the challenge was to adjust the position of my pelvis.

On later days I also found it helped to activate the obturators prior to heal strike and prior to activating sartorius and gracilis.

Even later I found out that activating tibialis anterior helped. I've mentioned that previously, as well as talked about obturator (and perhaps gemellus) activation. Something in particular with tibialis anterior that I found helpful was the idea of pulling up and out on the inner arch relative to the front of the shin. It was a tricky activation to learn, but it feels like now I can finally activate my left foot properly.

One other thing I noticed, and this was perhaps the biggest aha, was that I needed to pay some attention to my right hip.

With my pelvis biased to the right, I might have been balancing my upper body on my right hip joint. Shifting my pelvis more centrally, I need my right hip abductors (the outer hip muscles) to activate. This is to prevent my left hip bone from dropping relative to my right. It's also to help anchor the left side sartorius, gracilis, obturators and gemellii. This is in particular in the stage just prior to left heel strike.

And of course, I do have to try to apply this to running also.

The nice thing is, going through all of this problem solving has helped to give me a better understanding of my body. I hope it has helped you also.

Take out the slack

If you are interested in learning more about muscle control, I'd suggest trying out my take out the slack membership. It gives you access to all of my muscle control courses. And you can cancel at any time. There's about 22 hours of content, which if you are short on time can seem like a lot, but if you've done a 200 hour teacher training that might seem like only a little. But, it is a set of courses, each focusing on particular aspects of muscle control. I break the body down so that you can learn it easier and more effectively.

And the lessons are a lot like those I took when learning to ride a motorbike safely. For example we learned how to balance first, by pushing each other around with the engine not even on. We then learned how to use the brakes to the point that we could use them without having to think about how to use them. And that's what these lessons in muscle control aim to do.

They give you exercises for learning particular aspects of muscle control and practicing it so that you don't have to think about how to feel and control particular muscles. At the very least you'll understand what you need to practice so that you can get on with practicing and improving your ability to feel and control your body.

And indeed, at one point I called these lessons "driving lessons for your body".

The more

Published: 2018 08 02

Updated: 2018 08 16

Janu Sirsasana A with torso upright

Janu Sirsasana A with torso upright Marichyasana A with torso upright.

Marichyasana A with torso upright. Trying to stand up while keeping the lifted leg pulled forwards can be challenging for the standing leg.

Trying to stand up while keeping the lifted leg pulled forwards can be challenging for the standing leg.