Transverse abdominis function, toc

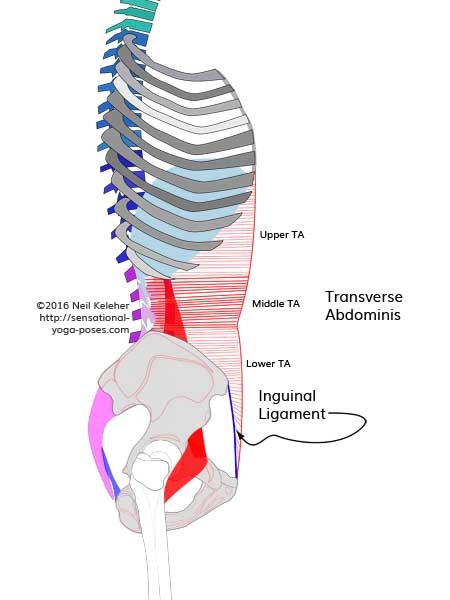

The part of the Transverse Abdominis that attaches to the pelvis attaches to the points of the hips, called the ASICs or Anterior Superior Iliac Crests, and the ligaments that mark the border between the belly and the inner thighs, the inguinal ligaments. (Fibers may also attach to the front portion of the iliac crest. We can include these fibers in this part of the TA).

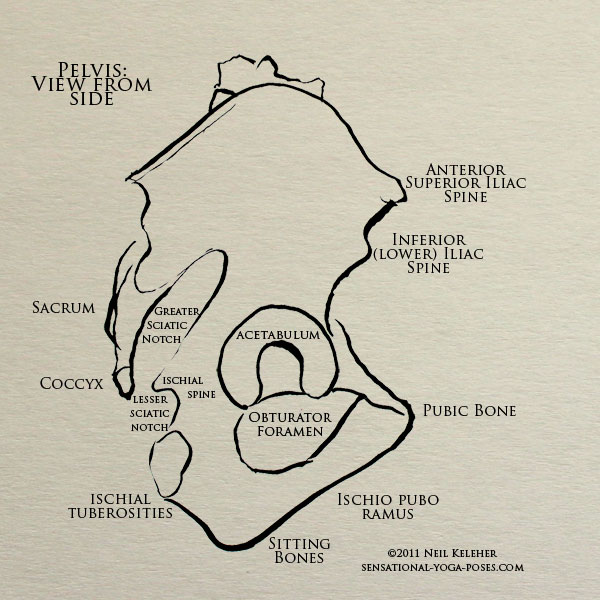

To understand how this lower portion of the transverse abdominis works we can model the pelvis as having two halves that hinge at the pubic bone and SI Joints. Two sets of references we can then use include the points of the hip bones, the ASICs or Anterior Superior Iliac Crests and the two bones that you feel when sitting on a hard chair, frequently called sitting bones but more technically the ITs or Ischial Tuberosities.

Pulling inwards on the ASICs causes the two halves of the pelvis to hinge so that the ITs move outwards, away from each other. Doing the opposite movement and pulling the ITs inwards hinges the hip bones so that the ASICs move outwards.

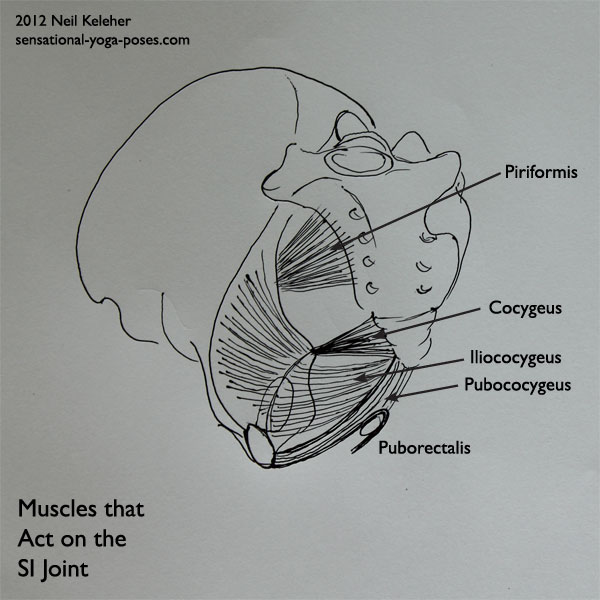

The lower portion of the Transverse abdominis can be used to pull inwards on the ASICs causing the ITs to spread apart. Meanwhile the pelvic floor muscles can be used to pull inwards on the ITs causing the ASICs to spread apart. In general activating the lower transverse abdominis causes the pelvic floor muscles to activate and vice versa.

When the lower Transverse Abdominis are used to pull inwards on the ASICs, the pelvic floor muscles also activate to resist the outward moving ITs. This is to help control the hinging of the two halves of the pelvis and stabilize the Sacroiliac Joints.

This dual activation is similiar to what happens when deliberately flexing your biceps. The triceps automatically activate to oppose the biceps. This dual action stabilizes the elbow joint.

The dual action of transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles stabilizes the SI Joints. It's for this reason that some yoga teachers suggest activating mula bandha to create uddiyana bandha. Activating one automatically causes the other to activate.

Mula Bandha is one way of saying "Activate the Pelvic Floor muscles."

Uddiyana Bandha is a way of saying "Activate the Lower Transverse Abdominis".

Going back to the "flexing your biceps" example, you could cause your biceps to activate with the elbow bent by focusing on contracting your triceps.

How do you activate the lower transverse abdominis? Pull inwards on the ASICs.

How do you activate the pelvic floor muscles? Because the pelvic floor musculature consists of a fan of muscles, activating the pelvic floor is a little bit more complex.

It can start with pulling the tailbone forwards towards the pubic bone.

Then pull the sitting bones inwards.

Then create a fan of tension from the sitting bones forwards to the pubic bone. Finally pull forwards on the anus and on a point just in front of the anus.

(This latter instruction may have to be varied for women).

Since the pelvis hinges (sort of) at the SI joint, the dual action of the Lower transverse abdominis and Pelvic Floor Muscles can help to stabilize the SI joint. However, having the pelvic floor muscles constantly activated (or constantly relaxed) is not a good thing. These are muscles and they are designed to activate and contract. In this regard it helps to understand that some of the hip muscles act on the SI joint. They can stabilize it directly via nutation or counter-nutation. Or they can affect it indirectly by anchoring the hip bone.

Hip muscle action can stabilize the SI Joint automatically. As a result, if the hips are stable (or at least one of them is, say in a balancing on one leg pose) there may be no need to activate the lower transverse abdominis and pelvic floor to stabilize the sacroiliac joint. The hip muscles take care of it.

Part of what resists the action of the transverse abdominis at the back of the sacrum is a layer of connective tissue called the Thoracolumbar Composite. This is a fused mass of connective tissue made up of layers from the erector spinae aponeurosis and various other layers of the thoracolumbar fascia. This fascia connects to both sides of the back of the pelvis where it extends beyond the back of the sacrum.

When the Transverse Abdominis engages, the Thoracolumbar composite resists the back of the pelvis being pulled apart. The ischial tuberosities spread apart instead.

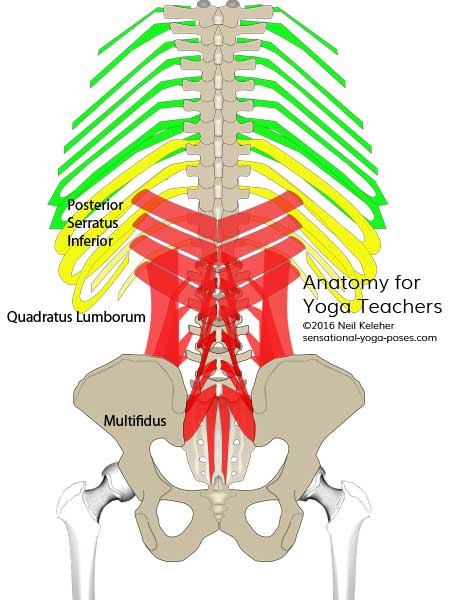

The thoracolumbar composite forms a pocket with the back of the sacrum. The spinal erectors, and the smaller posterior spinal muscles called the multifidus are sandwiched within this pocket between the back of the sacrum and the front surface of the thoracolumbar composite. Some fascicles of the multifidus attach to the front surface of this layer of fascia and so when tension is added to this fascia by the action of the lower transverse abdominis these multifidus muscles have a firm foundation from which to activate on the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae to which they attach. (These muscles also attach directly to posterior sacroiliac ligaments.)

The bottom-most lumbar vertebrae, L5 sits between the crests of the pelvis and it is part of the network of ligaments that bind the sacrum to the two hip bones. Activation of the lower transverse abdominis also possibly affects the stability of this vertebrae relative to the sacrum and relative to the hip-bones/pelvis.

With the sacrum and L5 stabilized relative to each other and relative to the pelvis this potentially creates a foundation for stabilizing the remaining portion of the lumbar spine.

Related:

Multifidus

Sacroiliac Joint Stabilization, SI Joint Exercises,

Mula Bandha

Pelvic Floor Muscles

Thoracolumbar Fascia

The middle portion of TA attaches to the lumbar vertebrae via the bits of bone that stick out the sides of these vertebrae, the transverse processes. It's aponeurosis (which is sort of like a tendon but multilayered) blends with the thoracolumbar fascia prior to attaching to the spine. Despite this, the fibers of the Transverse Abdominis are discernible within the mass of the thoracolumbar fascia.

One part of the thoracolumbar fascia is the Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath. This is a tube of connective tissue and bone that envelopes the posterior muscles of the spine (multifidii and spinal erectors both included). The aponeurosis of the Transverse Abdominis makes up most of the front wall of this sheath before it attaches to the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae.

It is also very interesting to note that the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominis passes behind the Quadratus Lumborum (QL) muscle prior to attaching to the lumbar spine. The QL attaches to the back of the upper rim of the pelvis and from there its fibers reach up to attach to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae as well as the lowest pair of ribs (the 12th pair). A second layer of this muscle also sometimes exists and has fibers in the opposite direction reaching down from the lowest pair of ribs to attach to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae.

While trying to draw the QL and TA it became fairly obvious that the transverse abdominis passes behind the quadratus lumborum and this raised the idea that tension in the TA could perhaps cause tension in the QL. One possible scenario was that if the lumbar spine was straight then Transverse abdominis activation could pull the QL inwards towards the front of the body adding tension to the muscle enabling it to better activate.

Also because of the close contact between the two muscles, tension in one could at the very least act as a signal to the other to activate or relax as required.

Recalling that activation of the lower transverse abdominis is resisted by the Pelvic Floor muscles, it would seem to make sense that other muscle also comes into play to resist the action of the Middle transverse abdominis. The combined pull of both the TA and QL on each lumbar vertebrae would be slightly forwards (due to the TA) and downwards (due to the QL.)

Another muscle that also has attachments to the lumbar transverse processes is the psoas. By itself it also can create a forwards and downwards pull on the lumbar vertebrae.

The lumbar multifidus attaches to the mamillary processes of the lumbar vertebrae. The fascicles of this muscle reach upwards from these processes to attach to the spinous process of the vertebrae one or two levels above. The forwards and downwards pull of the TA and QL combined could stabilize the vertebrae in such a way that the multifidus have a foundation for creating a downward pull on the spinous processes of the vertebrae to which it connects.

Pulling the middle later of the transverse abdominis inwards will eventually add tension to the rectus abdominis causing it to pull the sternum and pubic bone towards each other. Activation of the QL and Multifidus could act to resist this tendency helping to stabilize the lumbar spine.

If the lower layer of the transverse abdominis were also activated then both the sacrum and lumbar multifidus would potentially be activate creating stability in the SI joints as well as the lumbar spine.

Something that I figured out a little late in the game is that when the transverse abdominis is contracted past the border of the ribcage and pelvis, it actually stretches or lengthens the overlying obliques and rectus abdominis. So what you then have is the transverse abdominis activating and shortening while the obliques and rectus abdominis are lengthening.

If you the ribcage and pelvis are kept stationary, then the obliques and/or rectus abdominis can potentially activate to resist being pulled in. If the ribcage and pelvis are kept stationary, the obliques and/or rectus abdominis can exert against the spinal erectors, in particular the iliocostalis and longissimus (both of which have fibers that attach to the backs of the ribs.)

Activating the middle layer of the transverse abdominis can be as simple as pulling your belly button towards you spine. However, rather than just focusing on your belly button try to pull rearwards on the belly about an inch or two both above and below the belly button.

Once you have this action in isolation try it in combination with the action for activating the lower transverse abdominis. Activate the lower TA first, then the middle TA.

Another option is to draw two imaginary lines upwards from the ASICs (one line from each) to the bottom front corners of the ribcage. Draw these two lines inwards, towards each other, and rearwards.

Work at keeping your ribcage and pelvis stationary, i.e. prevent the sternum from drawing towards the pubic bone and vice versa. You may notice a downward pull on the backs of your ribs as a result.

Related:

Psoas Muscle

I never gave much thought to the upper transverse abdominis until some experiences in a Qi Gong class and some pain at the junction of my thoracic and lumbar spine during forward bends.

I felt pain in the region of T12/L1 in forward bends, particularly when I wasn't focusing on lengthening my spine or on using my arms. Why didn't I just lengthen my spine and reach with my arms? Because I wanted the option not to have to do that while doing forward bends.

And thus I started to explore the Posterior Serratus Inferior, a set of muscles that reaches downwards and inwards (or caudally and medially) from the lower four ribs to attach to the spinous processes of the lower two thoracic and upper two or three lumbar vertebrae.

I found that I could activate this muscle (with a reasonable degree of surety) with a combination of first lifting the backs of the ribs and then creating a downward pull on the lower three ribs. I found that doing this helped alleviate the sharp pain at T12/L1 while doing forward bends. Because of my Qi Gong class I also figured out that activation of the posterior serratus inferior also caused the upper band of the transverse abdominis to activate.

This was important in the Qi Gong class I attend since I then found it easier to take impacts to the solar plexus.

Because of the reverse in curvature of the spine at the junction of T12 and L1, and perhaps just because of the shear convenience of having structures like the ribs to hang muscle from, the PSI works in a similiar way to the Multifidus/QL combination. Using the ribs as anchors (which may in turn be anchored by action of the intercostals, or perhaps the levator costalis muscle) it pulls upwards on the spinous processes of the vertebrae using the ribs as anchors. The upper transverse abdominis seems to activate to resist this action, thus stabilizing the lower part of the ribcage as well as the junction of the lumbar and thoracic spines.

For those interested in the shape of muscles, it may be interesting to note that the pelvic floor muscles form a fan shape with the fan originating at the tailbone. The quadratus lumborum forms an upward pointing chevron pattern, and if the second layer is present, also a downwards pointing chevron. The serratus posterior inferior also forms a downwards pointing chevron.

To activate the upper transverse abdominis try pulling inwards (towards the center-line) on both sides of the arch of the ribcage. Once you have the inward pull you can also try creating a slight rearwards pull.

You an also play with activating the posterior serratus anterior to get the upper transverse abdominis to activate. Once you can activate this portion of the TA try it in combination with the other two portions, starting with the lower, then the middle then the upper portion of the TA. Then try keeping them active while continuing to breathe.

One way that you can use the transverse abdominis is to pressurize the abdomen. In this case it will work against (or in concert with) the respiratory diaphragm and the pelvic floor muscles to pressurize the abdominal organs. Personally, I don't find this very comfortable. (The sensation is similiar to what you get if you try "pushing" while going to the bathroom.)

An alternative is based on what was mentioned in the section on the middle transverse abdominis. When the transverse abdominis is pulled past the border of the ribcage and hip bones, it actually works against the obliques and rectus abdominis (as well as against the pelvic floor muscles and serratus posterior inferior) and also against the spinal erectors. Because it can pull inwards on the obliques and rectus abdominis, it can then vary the length and tension of these muscles.

And so a suggestion is to first practice transverse abdominis activation with the spine neutral. Also try it with the spine bent forwards, backwards and to the side. In each case you can vary the amount of "inwards pull" of the transverse abdominis. You could even experiment with pulling in on one side more than the other, particularly when side bending the spine. Try the same thing while twisting your spine.

Some of these are covered in transverse abdominis training.

You can play with sequenced activation of all three bands or isolated activation of only one or two bands.

Published: 2020 08 16

Updated: 2021 03 23